A new study from the University of Vienna on the inner ear in mammals offers valuable evidence and insight, while upending at least some of the conventional wisdom by finding the shape of the ear in some lineages is more directly connected to habitat and lifestyle than genetics alone.

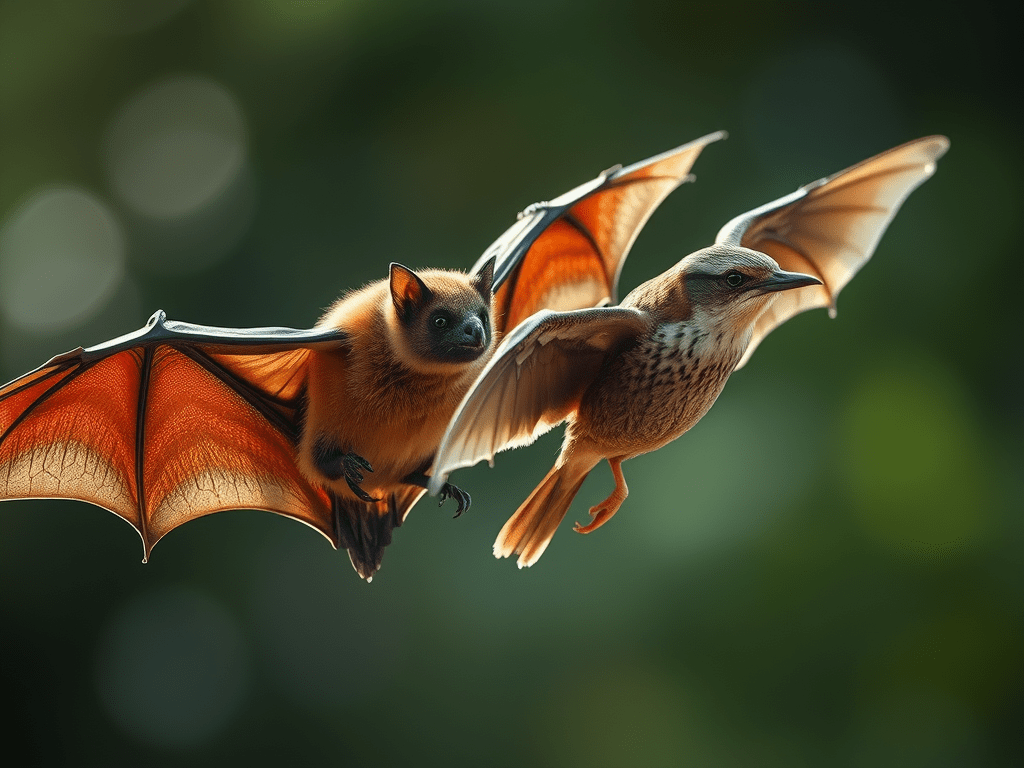

Counter intuitively, we can find evidence for evolution even when the principle tenets, heredity with variability and selection pressure, aren’t present in the first place. The process is known as “convergent evolution,” meaning that two different lineages, whether plant or animal, separately evolved the same structures or strategies to improve their reproductive success. In other words, the recipe (the genotype) might be different, but the cake either looks or tastes the same (the phenotype). We might not always be aware of it, but this fact is all around us, almost every time we look at the natural world, even right outside our own windows. Birds and bats both have wings, but their development isn’t guided by the same sets of genes and they have a totally different bone structure even beyond the use of feathers or fur. Humans and flies both have eyes, but the genetic underpinnings, the mechanisms, and some of the chemical processes are widely divergent. Simply because something looks the same or seems to serve the same function, doesn’t mean it arose the same way. Unlike a line of products designed by a human engineer, where a company will benefit from economies of scale by using the same parts on the same assembly line, intentionally streamlining the manufacturing process for maximum efficiency and hopefully profitability, evolution can only act upon the genes stored within a pair of mating individuals at a specific point in time. Outside of bacteria, which can share genes directly with one another via an exchange mechanism impossible for complex organisms, a bat cannot mate with a bird because flying would be a tremendous evolutionary advantage, nor can it steal the secret to the bird’s wings somehow. No, the proto-bat needed to assemble its own wings from what was present in their own proto-mammalian DNA at the time, and couldn’t simply cheat off another organism’s notes. At the same time, there are some strategies and structures that are so advantageous that evolution has produced them over and over again in different species using different genes. The wing for example has evolved at least four times, in birds, bats, pterosaurs, and insects. The eye has evolved even more frequently. Estimates put the ability to capture information from the environment using light sensitive apparatus having arisen 40, 50, or even 1,500 times. There are currently about 10 different designs for the eye present in living animals. It’s as though the tree of life were organized as different car companies. Toyota and Honda design and manufacture different cars in (mostly) different ways, but there are some aspects of an automobile, four wheels, brakes, a steering wheel, a driver’s seat, etc. that are so important, every car has them. While there are a few animals that make do without vision to fill certain ecological niches, having sight is so fundamental to success we can think of these outliers as being vehicles designed for a specific purpose that fail to conform to the normal layout.

I mentioned that this could be considered counter intuitive earlier for two reasons. First, these convergent structures are not related to one another on a genetic level and therefore can’t simply be studied directly as we look at how organisms have evolved from their ancestors, as we might when we consider why humans are different from our more ape-like cousins. They remain critical to the study of evolution, however, because they make it possible to connect different lineages together, understanding how evolution has repeatedly evolved the same strategies in response to the same or similar challenges. The wing of a bird and the wing of a bat have two radically different designs, but because they share the same purpose, we can attempt to unravel the conditions under which each arose and more generalize the theory. Second, because evolution has often been criticized for creating structures that seem far too complex to have arisen naturally. How could something as random as blind chance produce the eye? It has to have been designed, some say, the same way we would discover a watch on the beach and assume someone left it there, but knowing it has arisen by natural selection dozens of times, strongly suggests that our subjective assessment of the odds is fundamentally incorrect and we are looking at the problem the wrong way. Once might be chance, however impossible it might seem to use, twice might be coincidence, but three, four, or more times indicates that there are forces in play, operating unseen behind the scenes that we might not fully understand or even be aware of. Sometimes, this is referred to as the “evolution of evolvability,” meaning that as organisms evolve down their individual genetic lineages, there is another level of selection happening that favors more generalized increases in flexibility and adaptation, allowing new structures to arise more quickly and easily than they had in the past. To reuse the manufacturing analogy, Honda and Toyota do not simply need to make great cars. They need to adapt how they make cars to build them faster and better, and to make it easier to build new models from the same assembly line. The Camry and the Accord might both be excellent vehicles today, but in the future, the company that can more quickly and reliably keep its models up to date, will have a significant advantage over time, especially if the competitor needs to restart their operations from the ground up every time.

This makes sense in principle, but science requires evidence in practice, not mere musings and speculation. In that regard, a new study from the University of Vienna on the inner ear in diverse groups of mammals offers valuable evidence and insight, while upending at least some of the conventional wisdom. Researchers used the latest three dimensional imaging and modelling techniques to analyze the inner ear of Afrotheria, a group that includes animals as diverse as aardvarks, elephants, golden moles, hyraxes, elephant shrews (small rodents), and sea cows. The shape of Afrotheria’s inner ear was then compared with other mammals from different lineages with divergent genetic histories, but that have similar anatomy, live in a similar environment, or exhibit similar behaviors. These include anteaters, so-called “true moles,” rodents, hedgehogs, and even dolphins. Generally speaking, the researchers found that the shape of the ear was more closely aligned with anatomy, environment, and lifestyle than with genetics alone. In other words, animals that were close together genetically speaking, having a more recent common ancestor, had ears that were more measurably different than those who shared a habitat or some other factor. “We found that the inner ear shape is more similar between analogous species than between non-analogous ones, even when the latter share a more recent common ancestor and are therefore more closely related,” explained Nicole Grunstra, a lead author. For example, sea cows are much closer genetically to an elephant or a hyrax, but given their underwater lifestyle, their ears were more similar to dolphins, even though they are only distantly related. “We were also able to show that eco-morphologically similar mammals evolved similar ear shapes as an adaptation to shared ecological niches or locomotion, rather than by chance,” added senior author Anne Le Maître. Thus, the aardvark and the anteater are closer together in the shape of their ear, than the elephant shrew and the sea cow. This is convergent evolution in action, but it was surprising because other studies on birds and lizards suggested the opposite finding. The similarities in their ears appear to be primarily driven by genetics, rather than converging together based on habitat or behavior.

The discrepancy, however, could be the result of the evolution of evolvability. The mammalian ear is significantly more complex than either birds or lizards. In addition to having more parts, the middle ear itself is separate from the jaw bone, rather than attached to it. This enables mammals to have better hearing in general, especially at higher frequencies, but it also frees the ear to develop more divergently, not being bound to another structure and with more components to reposition, which might well make it more flexible from an evolutionary perspective. Therefore, mammals can evolve a wider variety of ears more perfectly suited to the environment with less changes to their genes than our avian and reptilian counterparts. “An increase in genetic and developmental factors of a trait gives natural selection more knobs to turn, which facilitates the evolution of different adaptations,” explains co-senior author Philipp Mitteröcker from the University of Vienna. As an ideal next step, an enterprising team of scientists should map the relevant portion of the Afrotheria genome and the other species involved in the study, and conduct a comparative analysis to determine what small changes in the Afrotheria genes produced big changes in the phenotype of the ear, and whether or not any genes map directly to their counterparts in other mammalian lineages, meaning some gene itself might have arisen twice rather than just the structure. Incredibly, it’s also conceivable that in some cases there will be no measurable change in the genome even though the ear is markedly different. While this is unlikely, different environments can create different bodies from the same genes, or the changes could be the result of gene mutation or copying, rather than an actual mutation. Either scenario would be evidence of the evolution of evolvability in action, a discovery of no mean importance even in what may seem like a relatively minor context. In evolution, however, we are increasingly finding that no detail is beneath the notice of natural selection, nor is any change in a gene too small to produce outsize results. Counter intuitive, indeed.