Dan Aykroyd in blackface? The N-word? Greedy capitalists? A rape by an ape? On the problematic side, Trading Places has it all, but if you look beneath the surface these aspects are all in the service of a downright progressive theme. Of course, the woke are incapable of doing so…

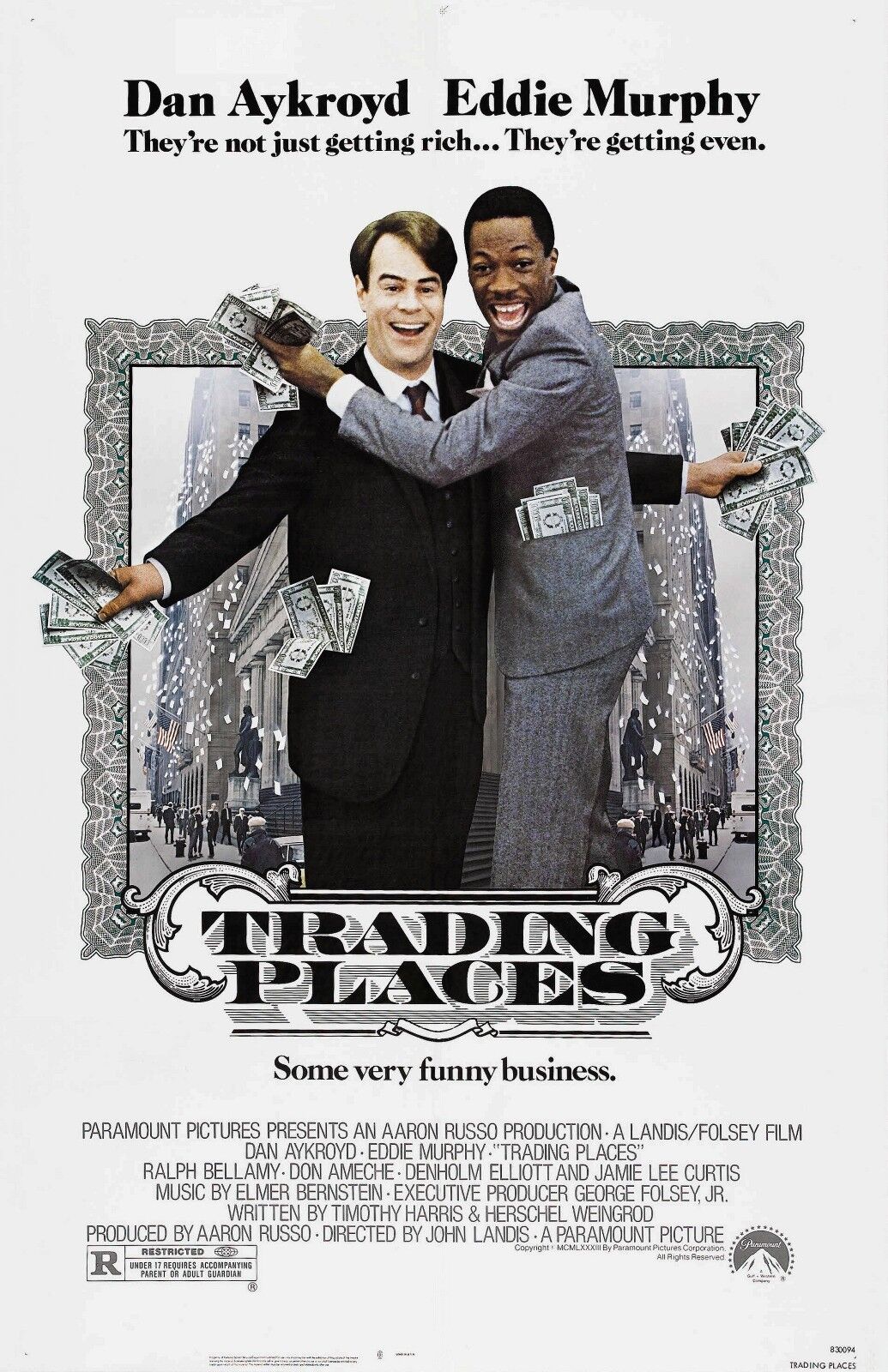

To claim Trading Places, the 1983 Christmas comedy starring Eddie Murphy, Dan Aykroyd, and Jamie Lee Curtis about a social experiment over the role of nature versus nurture in our lives, is problematic by modern standards is an understatement. Mr. Aykroyd actually appears in black face as some kind of caricature of a Rastafarian in a famous sequence, partnering with Eddie Murphy, who is in close to a mockery of traditional African garb, to recite some kind of bizarre cheer from an African Studies conference that can only be seen as mocking indigenous languages. (Mr. Aykroyd himself has since said that he “probably wouldn’t choose to do a blackface part.”) The film contains the line, “Of course there’s something wrong with him, he’s a negro,” referring to Mr. Murphy’s Billy Ray Valentine character. The N-word appears. A man is raped by an ape, and mocked for it in one of the more memorable and hilarious sequences. The white characters are not generally depicted as fine, upstanding people by any means, but they are at least wealthy and polite, if insufferable, see the Harvard crew singing about their time in the Ivy League. The black characters outside of Mr. Murphy are, in comparison, poor, what Murphy himself describes as “free loaders,” uncouth, and generally a half-step above 1970’s style pimps and hookers. As a result, the film was generally lauded on its release, earning close to $100 million domestically and becoming an instant 80’s classic, only to be reconsidered in recent years. “If you’d asked me yesterday what I thought of Trading Places I would confidently tell you that it is one of those instant classics that fundamentally just works. I’d say that it has a terrific, brilliantly structured screenplay and features a perfectly cast Dan Aykroyd and Eddie Murphy at their very best. I’d hail Trading Places as part of director John Landis’ golden age and praise its iconic scenes and famous lines,” explains Nathan Rabin on Substack. “If you were to ask me what I thought of Trading Places now, however, I would sigh audibly and, with a pained expression, wearily concede that I found it racist, sexist, classist and intensely bourgeoisie and capitalist. Also, unfunny.” In addition to the blackface, Mr. Rabin is incensed that Mr. Murphy is “unmistakably playing a caricature and not a terribly progressive one either.” He calls a woman a “bitch,” uses gay slurs in a movie with no gay characters. Meanwhile, Ms. Lee Curtis’ portrayal of the prostitute, Ophelia, “proudly tells Louis that she had no pimp, doesn’t use drugs and has amassed forty-one thousand dollars from her employment in the sex trade and plans to retire in three years. Ophelia is a capitalist and an aspiring yuppie. In Trading Places that’s the best thing to be. It’s okay to be a hustler or a sex worker or even a servant as long as you have aspirations to do something more to make more money.” None of “this would matter if Trading Places was anywhere near as funny as I remembered it being. But I didn’t laugh a whole lot watching Trading Places for maybe the fourth or fifth time.”

Setting aside the now standard progressive re-evaluation process of all things not created in the last week, wherein movies that contain problematic content by modern standards – and Trading Places certainly does – are immediately declared to be not as good as they originally thought, amazing how that works, there is another interpretation of the movie that is forward thinking, if not decades ahead of its time, one where what is problematic should largely have been seen as such when it was released forty years ago. To a large extent, criticisms such as Mr. Rabin’s are only criticisms if you view the world through a hierarchy of oppression, where racism and sexism are at the top of the pyramid, crimes that are somehow more heinous than others, even when by objective measures they are surely not and, in fact, they exist in the world of the film to highlight the flaws of the characters themselves. The antagonists, Randolph and Mortimer Duke, are racists, yes, but why is that necessarily worse than their other less than desirable traits, much less what they actually bring to fruition during the course of the movie? The two set events in motion by betting whether or not they can destroy a wealthy, well-educated white man and elevate a poor, downtrodden black man as a social experiment to determine the role of nature and nurture in our lives. To do so, they have no compunction at all about framing Mr. Aykroyd’s Louis Winthorpe III for a crime he did not commit, planting PCP on him, freezing his bank accounts, ejecting him from his home, denying him his car, separating him from his admittedly frivolous fiancée and friends, and leaving him completely homeless. That Louis did absolutely nothing to deserve the crime committed against him is irrelevant to Duke and Duke’s plans. Though he is rich and white, he is still a toy to be played with at their whim, meaning there is no white privilege and he is the same as Mr. Murphy in their eyes; perhaps even worse, when he ultimately succumbs to the crushing poverty they’ve inflicted upon him by choice, both blame him for the failing and choose to consign him to his fate. Likewise, even after Billy Valentine proves himself adroit at the job, a hit with his coworkers, and increasingly refined in his manners, they refuse to keep him on as Managing Director simply because he’s black. Further, we get the sense that this is not their first bet and they have done the same or similar before, not to mention one of their plans is to steal a confidential crop report to manipulate the market and make even more money. These two are evil, period. They have no redeeming qualities. The racism, sexism, and classicism they display is a symptom of a far deeper deficit of character, not the other way around. Viewed from this perspective, one is not supposed to watch the film, either in 1983 or today, and embrace the problematic aspects. We are instead supposed to sympathize with the characters those aspects are directed towards.

Therefore, Duke and Duke are only thwarted in their nefarious schemes because Mr. Murphy’s Billy Valentine has an agency frequently lacking even in modern movies. He might no longer fit in with the poor people he previously associated with, but he makes a clear, colorblind choice that is critical to the outcome. There might well be some stereotypical aspects of his character, as there are for almost any character for that matter, but ultimately the entire movie hinges on him overhearing the Dukes discuss the bet and then seeking Mr. Aykroyd out to partner with him to get their comeuppance. As Billy Valentine himself explains it, “You know, it occurs to me that the best way you hurt rich people is by turning them into poor people.” It is this unexpected partnership between black and white, rich and poor, a partnership begun by the black man, meaning it cannot be dismissed as the white savior trope, that underlies the entire climax. Though both have been horribly taken advantage of by Duke and Duke, it is Eddie Murphy that saves Dan Aykroyd, and assembles the team that will defeat the antagonists. Dan Aykroyd’s Louis would by all accounts have perished in poverty, if not actually killing himself, were it not for Billy Valentine’s intervention. As they plan their revenge, they are joined by Jamie Lee Curtis’ Ophelia, a sex worker that also has agency and exudes a – dare I say, downright modern – sex positivity. She is unapologetically a prostitute on her terms. She does so purely because it is the best way to achieve her goals, and she begs no favors, she owes no one anything in life, and refuses criticism from anyone while also being unafraid to show off her body – when she wants to. It is her kindness that takes Mr. Aykroyd in and likely saves his life given it is almost impossible to believe such a soft, pampered character could survive a single night on the streets. The group is rounded out by Denhom Elliot’s British butler, who served Mr. Aykroyd at the beginning of the movie and then abandons him for Mr. Murphy at the Duke’s request. He too has the agency to realize the Dukes are evil, and join the cause against them. That the quartet believes they can make money in the process should not be seen as a flaw in any sense because it’s hard to believe they will do with their riches what the Dukes did. Putting this another way, the good guys are good not because of their money or lack of it, but because of their inner morality. The bad guys are bad, not because they have money though they use it as a means to their ends, but because they have no morality. Money is the currency that drives the film from the opening frame, enabling us to explore these moral complexities. In the context of the film’s morality, why not make a buck while defeating your enemies? If money was the goal, they could simply have blackmailed the Dukes after stealing the crop report themselves. Instead, they use that knowledge to trick and ultimately ruin them. That they were able to profit from it is an added bonus. What were they supposed to do, not make the money that was literally dangled right in front of them?

The film itself doesn’t exactly portray money, much less the acquisition of it through a Wall Street trading floor in a positive light either. First, Eddie Murphy is able to easily perform Dan Aykroyd’s job with barely any training and no education, and essentially relying on his gut instincts. From there, we can readily conclude that those who have money in the film, have it by accident more than anything else. Indeed, that is the reasonably clear moral of the story given the “bet” that sets things off is resolved in favor of nurture, not nature. One would need to completely dismiss the obvious conclusion that the white people in the film have money, power, and prestige solely because they were born in the right circumstances, and anyone born into those circumstances would likewise prosper. If anything, the film can be seen as a critique of classism, innate talent, striving for success, etc., and instead embraces an almost socialist worldview where – if everyone was given the resources they need – everyone would be happy and rich. Second, the film’s depiction of capitalism in action on an actual Wall Street trading floor in the final sequence isn’t exactly flattering. Up until that point, we haven’t seen what happens behind the scenes at a firm like Duke and Duke, only the luxury and ostentation on the surface, multiple levels removed from the monetary sausage making. The climax takes places on the actual trading floor, however, and Dan Aykroyd introduces what Mr. Murphy is about to witness by claiming “Think big, think positive. Never show any sign of weakness. Always go for the throat. Buy low, sell high. Fear, that’s the other guy’s problem. Nothing can prepare you for the unbridled carnage you are about to witness. The Super Bowl, the World Series. Pressure? Here it’s kill or be killed. Make no friends and take no prisoners.” This prompts Mr. Murphy to conclude, “We’ve got to kill the motherfucker…We’ve got to kill them.” Perhaps only in the eyes of the woke could such obvious meaning be inverted in the service of wokeness itself. If anything, the story is the opposite of what the re-evaluators claim it is – if you can look past some of the choices we might not make today, but of course that is near impossible for the woke, so obsessed are they with their hierarchies.

Of course, the true measure of a comedy is whether or not it’s funny. A good story, an interesting moral fable, strong characters and great performances, mean nothing if they aren’t in the service of humor. Humor is necessarily something very personal, but it’s hard to conclude that Trading Places is anything other than a rip roaring good time, the rare movie that combines laughs with true wit and interesting plotting. In 2015, the Writers Guild of America tied it for 33rd place with Ferris Bueller’s Day Off in the 101 Funniest Screenplays of all time. In 2017, the BBC polled 253 critics across 52 countries for their take on the funniest film ever made. Trading Places came in 74th, right beyond The Naked Gun and Mr. Murphy’s own The Nutty Professor. Obviously, the film sits in good company, and not surprisingly. The dynamic between Mr. Aykroyd’s straight man and Mr. Murphy’s crazy man is right out of the odd couple. The supporting cast seems like they were born for the roles, and together the film serves up everything from slapstick – who can forget Eddie Murphy’s first introduction to his new house, where he’s trying to steal everything that’s not nailed down right in front of the white people – to satire, such as Louis waking up in his bed after being saved by Eddie Murphy, only to remark, “I had the most absurd nightmare. I was poor and no one liked me. I lost my job, I lost my house, Penelope hated me, and it was all because of this terrible, awful Negro!” When one of the Dukes, who appear to have been bosom buddies throughout the movie, collapses after they realize they’ve lost all of their money, the other doesn’t care, “Fuck him! Now, you listen to me! I want trading reopened right now. Get those brokers back in here! Turn those machines back on!” Or this exchange, when Dan Aykroyd attempts to pawn his watch. “Fifty bucks? No, no, no. This is a Rouchefoucauld. The thinnest water-resistant watch in the world. Singularly unique, sculptured in design, hand-crafted in Switzerland, and water resistant to three atmospheres. This is the sports watch of the ’80s. Six thousand, nine hundred and fifty five dollars retail!” “You got a receipt?” “Look, it tells time simultaneously in Monte Carlo, Beverly Hills, London, Paris, Rome, and Gstaad.” “In Philadelphia, it’s worth 50 bucks.” Ultimately, Mr. Rabin’s reassessment of the comedic value – and presumably others like him – reveals the reality that the woke cannot interpret or appreciate anything outside their narrow, hierarchical worldview. Humor, to them, is simply another means to battle the demons of white supremacy and privilege. When it does not conform to this arbitrary limit, it ceases to be funny. Humor, meanwhile, is supposed to point out universal human foibles, as Trading Places so brilliantly does. Putting this another way, the failing is theirs, not the films’.