The Godfather is what most would consider the better movie by normal standards. A far more beloved and well-remembered film, but which rings more true today when most of us spend our days trapped behind computer screens?

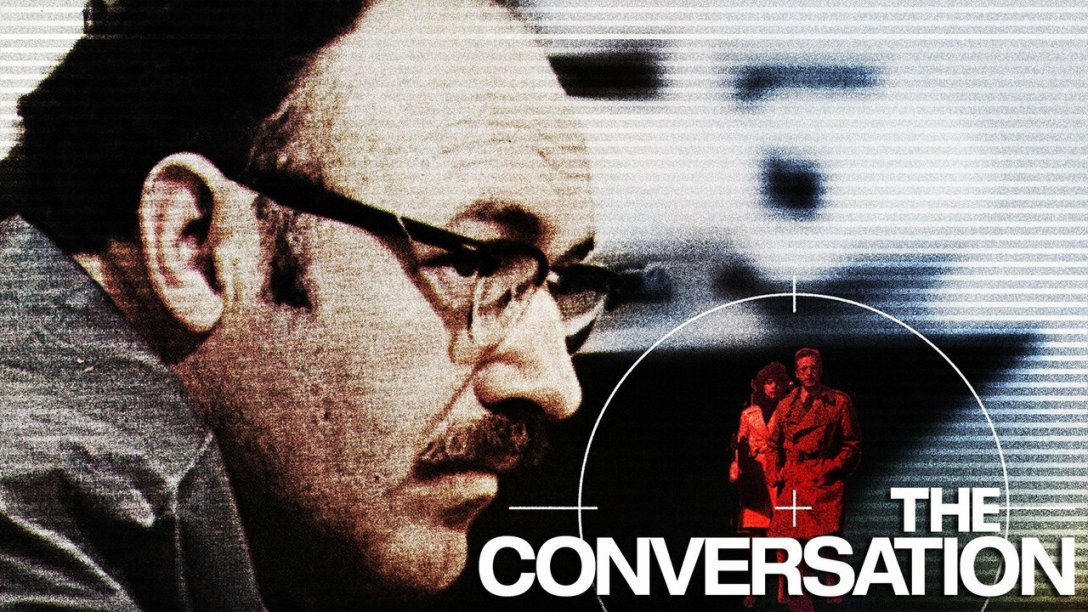

Legendary director Francis Ford Coppola somehow managed to direct The Conversation, what has proved to be an almost prophetic look at technology’s ever increasing ability to surveil anything and everything, in the very short window between his two much better known masterworks, The Godfather, 1972, and The Godfather Part II, 1974. In comparison to those two sprawling epics, which span continents and decades, The Conversion seems a smaller film on the surface, centered around one man, played with impeccable restraint by Gene Hackman, and his inability to escape a vague tragedy from his past as he considers the implications of his latest job. The plot, from that perspective, is similar to the neo-noir films that were popular at the time, including Chinatown, which was released the same year, and The Long Goodbye, released a year earlier. The trappings of these films are easily recognizable today, wherein a detective finds himself deeper than they expected as the job they took, perhaps against their better judgment, reveals a more sprawling criminal enterprise or conspiracy. Mr. Hackman’s Harry Saul is not a detective, however, and he is not investigating any crime. He is instead an expert in the relatively new field of surveillance, hired by government and private interests to procure information that others would prefer remain hidden. His specialty is eavesdropping, surreptitiously recording the conversations of his targets using whatever means necessary. His latest assignment is a couple. He does not know them, has no idea who they are, what they do, or what their relationship might be. He is given only a time and place, and a challenging one at that. Harry has been asked to record the conversation this couple has in a crowded public square, as they circle the park, practically whispering to one another. Mr. Coppola wisely dispenses with any backstory and instead plunges us right into this assignment, opening with a long shot of the square itself as the camera ever so slowly zooms in on the subjects, mimicking the technique’s Harry’s microphones use to eliminate background noise. The audio is used to cue the audience that this isn’t your normal establishing shot, mixing in static and other sound effects to indicate the conversation is being recorded before Harry and his team are revealed. The audio also obscures much of the couple’s conversation, lending an air of mystery to the proceedings that will linger throughout the movie. We learn more about the couple as Harry himself does.

From all outside appearances, there is nothing particularly special about them. They are almost entirely average, practically indistinguishable from everyone else in the crowd, nor do they talk about anything that we can tell that seems of high importance to anyone, and yet someone must’ve hired Harry to record them at this specific date and time for reasons that remain unclear throughout most of the film. Gene Hackman’s Harry is equally opaque at first. We understand that he’s an expert in his field, a private contractor, and that he has a near paranoid streak, not even having a phone in his apartment presumably out of fear it would be tapped. We know he has difficulties in relationships both with his colleagues and potential romantic partners. Some of these traits are familiar from the film noir genre, but rarely is the protagonist this soft spoken and reserved, incapable of making the kind of wisecracks that tend to define the classic private investigator, either as a means to keep his adversaries off-balance or a simple defense mechanism. Harry, by contrast, barely talks to his own employees, much less anyone else, a point made plain when his would-be girlfriend says she knows nothing about him, has never been to his apartment, and they never meet anywhere outside her apartment. The only levity in his life appears to be a penchant for jazz and perhaps the only time he appears relaxed is while playing the saxophone, alone in his own apartment. Professionally, the nature of his work differs dramatically from the classic “private dick” as well. The surveillance industry, even in the early 1970s, was driven by technology, machines that record, playback, and manipulate audio. Harry spends most of his time listening to, analyzing, mixing, and enhancing recordings, not out in the field and certainly not getting into any fisticuffs. In that regard, there is an obvious parallel to filmmakers themselves, Harry as Mr. Coppola to some degree, more on that in a moment. To obtain an optimal recording, Harry needs to organize his team in the proper places with the proper equipment, gathering the coverage he needs to return to his loft of an office and mix down the final product. This serves three purposes in the film, introducing us to Harry’s world as he works his magic on the raw recordings, filling out more details of the conversation itself, and showing us Harry’s rapidly increasing obsession with the couple. While most of their conversation is anodyne save for the bizarre circumstances of walking around the park on a regular basis simply to talk, Harry picks up one specific line that seems to contain a mystery of its own. “He’d kill us if he could,” the unknown man says to the unknown woman without any real context. Even on its own, the line suggests that the couple is having an affair of some kind and the husband is likely the jealous sort.

It’s enough to plunge Harry deeper into his obsession, especially after he is unable to meet with the mysterious director who hired him in the first place. Instead, he’s relegated to the director’s assistant, portrayed, interestingly enough, by a young Harrison Ford. The assistant assures Harry that he’s acting on the director’s behalf, offering him payment in full, $15,000, not a small fee in 1974, in exchange for the recording. Harry, however, has too much of a paranoid streak to deal with an underling he hasn’t met and refuses, almost fighting the assistant for the tape. As he is exiting the building, he sees both the man and the woman whose conversation he recorded, apparently employees of whatever company has hired him, further heightening his suspicions that there is something more to this job than he’d previously believed. He has also dug into the recording again, identifying another strange comment about meeting at a hotel room that coming Sunday. He cannot say anything clearly about what it means, or much of anything else, except he has grown increasingly concerned. This is not the way the surveillance industry is supposed to work, however. Harry isn’t supposed to care who he records or why, or what happens to the tapes. He’s a private contractor hired for a specific job for reasons above his pay grade as they say, and his increasing obsession with the recording and the machinations behind it alienates his own employees, further isolating him as the film progresses. This isolation and outright loneliness is made plain by a surveillance conference he attends before we move into the final act. There, it is equally obvious that he is something of a celebrity in the industry and also an outsider. He rebuffs a request to sponsor or endorse any technology he does not develop on his own, calls much of it junk, and meets his chief competitor in person for the first time. Harrison Ford’s assistant is also at the conference, demanding the recording, and prompting Harry to believe he’s being followed. After, a group including his chief competitor and his spokesmodel returns to the loft to keep the party going late into the evening, cleverly offering an opportunity to understand a little more of Harry’s backstory, what makes him who he is today. The chief competitor, who appears to be Harry’s opposite in all things, brash and outspoken, happy with his field, all that our protagonist is not, reveals that some years earlier Harry worked in New York City on a job concerning union corruption. The job has since become a legend because no one can figure out how he recorded the subjects on a boat in the middle of the ocean.

Harry isn’t interested in that. It does not seem to be a source of much pride, but he remains haunted that one of the parties and his wife was killed in the aftermath in retribution for revealing the scandal. This is something he’s vowed to himself will never happen again, even though he’s not supposed to care and none of his colleagues do in the least. The job is all that’s important and because no one can figure out how he did it, Harry is a legend in their eyes. Legends, however, also make easy targets, and so his chief competitor plays something of a practical joke, surreptitiously recording Harry’s private conversation with the spokesmodel, where he reveals that he’s in love with his would-be girlfriend and might have wasted his chance for happiness. Harry is outraged, kicks everyone out of the loft except the model, but even then he just wants to listen to the conversation one more time, desperate to know what it means. Who will kill them? What’s happening at the hotel that Sunday? Are there any other seemingly unimportant details he missed? A word or phrase with a double meaning? He lies on the bed, listening to the recording while she seduces him, but when he wakes up, he finds that she has taken the tape. The assistant calls him shortly thereafter, telling him they have it, and are still willing to provide payment. He is to meet with the director as well in his office, who is interestingly enough played by Robert Duvall in a short scene. When Harry arrives, however, he sees a photo and figures out who the woman is: The director’s wife. The two have a strange meeting and Harry leaves more distraught than ever, believing the director is going to use the knowledge of the affair and the meeting at the hotel on Sunday to kill his wife and her lover. At this point, he is in too deep as film noir tropes go and cannot help himself. He gets an adjoining room at the hotel, and listens in, but cannot make out the conversation. On the balcony, he believes he sees a bloody body pushed against the window and suffers something like a panic attack, collapsing on the bed. He breaks into the room after he recovers himself to find it clean and orderly, as though the maid had just been through – except for the toilet. Blood begins to bubble up and overflow, sending him from the room in a hysteric fit. He goes to meet the director again to confront him for his crime, only to discover that he had it wrong: The director’s wife and his lover were plotting to kill him, not the other way around. The director is dead and Harry receives final warning: They are listening to him, playing back a recording of him playing the saxophone in his own apartment. The movie ends with a scene inspired by Edgar Allan Poe’s classic “The Black Cat.” Harry rips up the entire apartment, walls, floorboards, and all, but cannot find the recording device. He can only take solace in his saxophone, alone and more paranoid than ever.

Fifty years later, the technology might be outdated, but there is no doubt that we live in Harry’s world when every phone call is logged by the government and we’re recorded almost everywhere we go, even by our doorbells of all things. Harry’s paranoia might have been a delusion then and some events in the final third of the film might not even have been real for all we can say. We know for certain that the director is dead because of a newspaper headline, but the blood from the toilet seems an over the top fantasy and Harry also experiences flashes of the director’s dead body he could not have actually seen given the room was sanitized when he finally broke in. Ultimately, however, it doesn’t really matter whether he’s going mad because he helped set these events in motion by recording the conversation in the first place. A career built on invading people’s privacy returns to haunt him, something he promised himself would never happen. Today, we are not Harry, but we are all of his subjects to some extent, especially knowing Google has a record of every key I type in this very article and given the ability of hackers to purloin information that is supposed to be protected, anything could be seized and leaked. In some ways, The Conversation is a “small film” as I mentioned earlier. It was shot on relatively tiny budget of $1.6 million over a period of three months, likely when Mr. Coppola had The Godfather II on his mind, wondering if he could live up to the beloved first installment. Though the script itself was written almost a decade earlier, one cannot help but wonder if some of Harry’s isolation, fears, and paranoia were Mr. Coppola’s own, in the shadow of his own masterpiece, doubting his ability to outdo himself. Small, however, doesn’t mean that it doesn’t address big ideas, which to some extent might overshadow his achievements in The Godfather Trilogy. The Godfather is fundamentally about family and power. The relationships we all have, the lengths we will go to protect them and the means we will use to leverage them to get what we want. The Conversation, in contrast, is about isolation and paranoia, what happens to a man who watches people for a living rather than simply living himself, becoming powerless to change his own fate in the process. The Godfather is what most would consider the better movie by normal standards. A far more beloved and well-remembered film, but let me ask you this, which rings more true today when most of us spend our days trapped behind computer screens, many of us isolated from our loved ones, watching other people’s lives go by, from surreptitiously spying on their social media feeds to binging reality TV on demand?

Image may be subject to copyright.