If only we could sleep as easily as we can die. I could end my life in an instant, but for reasons that defy explanation, simply putting the mind to rest for a few hours can prove impossible.

If only we could sleep as easily as we can die. I could, if I chose, end my life in an instant in hundreds, if not thousands of different ways, some more painful and gruesome than others, but for reasons that defy explanation, simply putting the mind to rest for a few hours can prove an impossible task. However much we wish for it and however tired we are, there are times when sleep will not come whatever we try. For some, this sad, frustrating state of affairs is an all too frequent occurrence. While estimates vary, around a third of people report occasional symptoms of insomnia while about fifteen percent having trouble falling asleep on a near-daily basis and a full ten percent suffer from it as a chronic condition. My own experience with the phenomena is primarily through the painful oddity of jet lag. Almost invariably, when I travel more than six hours outside my regular time zone, I have no trouble falling asleep the first night after an exhausting day of lengthy flights, but the second and third are a different story. Bizarrely, someone suffering from jet lag usually doesn’t have any difficulty falling asleep. For me at least, I got to bed without a problem, lights out as they say pretty much as soon as my head hits the pillow with no indication of anything out of the ordinary – only to wake back up barely an hour later. Even then, it’s not clear anything is amiss at first. For a few moments, I could’ve been asleep for most of the night until I check the time my phone and realize I’d barely been out at all. There is a short period afterward where I feel tired enough that sleep will return in short order, believing or more likely wanting to believe, that I’ll fall back asleep in no time, but I don’t. Eventually, I’ll try to read, listen to music, get up and walk around, anything, but it still doesn’t work for at least four hours, during which I am somewhat tired yet mostly awake. Somehow, the process repeats itself for the second night, even though I am up all day and should in a just world be able to get to sleep, but almost miraculously on the third, regular sleep returns.

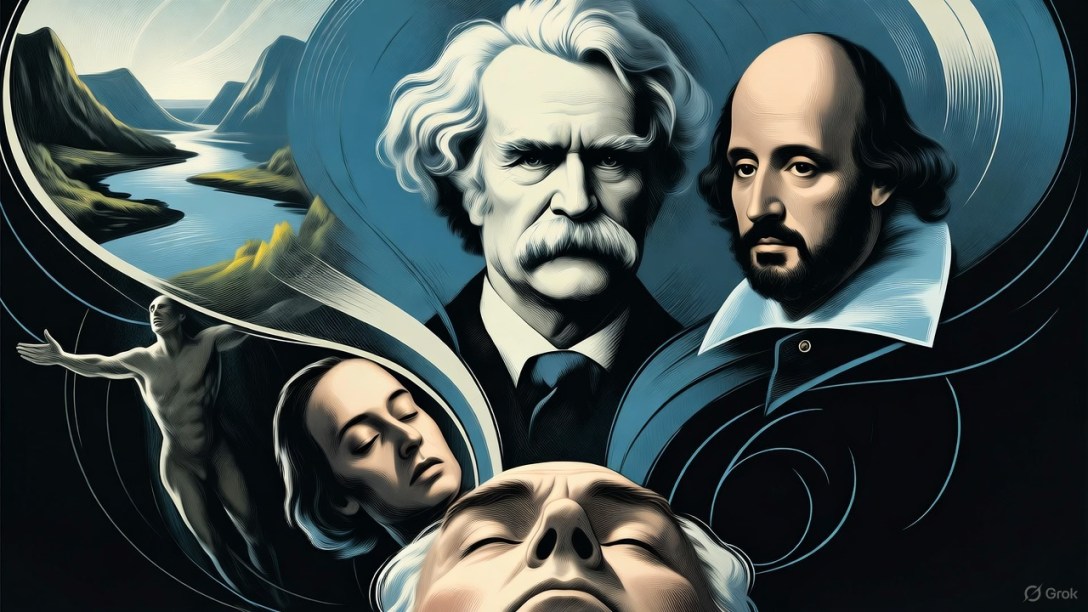

It was on one of those nights last week, while I was traveling to Dubai that this post came to me, not in its entirety, but in the vague random fashion of someone sleep deprived. Shakespeare, of course, compared sleep to death in the most famous speech in the English language. When Hamlet ponders whether something is to be or not to be, he wonders whether it is better to endure “slings and arrows of outrageous fortune” or simply end one’s existence, before proclaiming:

To die—to sleep,

No more; and by a sleep to say we end

The heart-ache and the thousand natural shocks

That flesh is heir to: ‘tis a consummation

Devoutly to be wish’d.

On one level, the connection between death and sleep is obvious. Outside of intoxication, sleep is the only time we lose consciousness for a prolonged period. While we are sleeping, we are not aware of the outside world, do not experience anything through our senses, and the little-voice inside our head turns off in a way that’s impossible when we are awake. Though our unconscious minds are still hard at work – causing our hearts to beat, our lungs to breathe, our other organs to function as ever – we do not know or feel any of it. In principle, if we were to die without waking up in a spasm of pain or terror, we would never know it either, passing on blissfully unaware, making the fact that we will wake up under normal circumstances perhaps the biggest leap of faith all of us take on a daily basis. We have no means of knowing we will actually return to our conscious selves, no control over whether we will successfully make this return, no ability of any kind to influence events, and yet few of us fall asleep wondering if the hazy, fragment thought that slips our mind at last is, in truth, the last one we will ever have. Instead, under most circumstances we take for granted that the body will do what it has always done before and turn the mind back on after we are properly, or at times improperly rested. It is worth noting that we have no choice in the matter either way. If we do not sleep, both our minds and bodies can suffer serious maladies. Even a single night without sleep can impact attention, judgement, memory, learning, reaction time, and hand-eye coordination, producing symptoms similar to being drunk plus accompanying anxiety, irritability, and stress – for me, at the tail end of the second day without sleep, my vision started to get blurry, as if the letters on my phone screen had ghosts around them. At between 48 and 72 hours without sleep, we can experience hallucinations and outright psychosis. For those with chronic sleep deprivation, the more physical effects include a weakened immune system, increased risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes and other metabolic issues, neurodegenerative disease, and even a decrease in the risk of mortality and a shortened lifespan. In that sense, we can say that we sleep quite literally to live.

At the same time, there is a certain life in sleep when we consider dreams, making it not entirely accurate to claim that we are always unconscious while we are sleeping. Though the consciousness of dreams can be different than that of being awake, we possess a certain level of awareness – at times a heightened one – we can act, make decisions, even judgements of a sort, and remember the experience, however strange, whether wonderfully so or more disturbing like a nightmare. To some, dreams are so powerful that they are another sort of life entirely, a world different yet equal to being awake in a meaningful way. The legendary humorist, satirist, and critic of human nature Mark Twain fervently believed that was the case and indeed acknowledged no real superiority or distinction between one or the other, reducing everything both to a dream in and of itself. As he put it, “Nothing exists; all is a dream. God – man – the world – the sun, the moon, the wilderness of stars – a dream, all a dream; they have no existence.” He went on to emphasize the reality of the dream world itself, viewing what happens there as real as when we are awake, even suggesting it is somehow more permanent, “In our dreams – I know it! – we do make the journeys we seem to make: we do see the things we seem to see; the people, the homes, the cats, the dogs, the birds, the whales, are real, not chimeras; they are living spirits, not shadows; and they are immortal and indestructible. They go whither they will; they visit all resorts, all points of interest, even the twinkling suns that wander in the wastes of space. That is where those strange mountains are which slide from under our feet while we walk, and where those vast caverns are whose bewildering avenues close behind us and in front when we are lost, and shut us in. We know this because there are no such things here, and they must be there, because there is no other place.” He might’ve come to this conclusion at least partly because he seemed a different person in dreams with different talents, sometimes the opposite of who he was when he was awake. In the waking world, he had an incredible literary sense (obviously, considering the classics he penned), but a poor artistic one, unable to visualize his memories, reducing everything to a blur, but in dreams Twain insisted he could see and remember more clearly, writing “my dream-artist can draw anything, and do it perfectly; he can paint with all the color and all the shades, and do it with delicacy and truth; he can place before me vivid images of palaces, cities, hamlets, hovels, mountains, valleys, lakes, skies, glowing in sunlight or moonlight, or veiled in driving gusts of snow or rain, and he can set before me people who are intensely alive, and who feel, and express their feelings in their faces, and who also talk and laugh, sing and swear.”

The “To be or not to be speech” is also keenly interested in dreams, albeit imagining them for a different purpose. After equating sleep with death, Hamlet goes on to worry about what dreams one might experience when they were dead, assuming they could be radically different from those we experience while alive and insisting this fear of the unknown is why most people don’t commit suicide given the vagaries and cruelties of our mortal existence:

To die, to sleep;

To sleep, perchance to dream—ay, there’s the rub:

For in that sleep of death what dreams may come,

When we have shuffled off this mortal coil,

Must give us pause—there’s the respect

That makes calamity of so long life.

After detailing the “whips and scorns of time” and the other weights we bear as creatures confined to this Earth, Hamlet claims it’s only “the dread of something after death, The undiscover’d country, from whose bourn No traveller returns, puzzles the will, And makes us rather bear those ills we have Than fly to others that we know not of?” Here, Hamlet slips from the idea of a temporary dream in the sleep of death to a vaguer and yet more terrifying notion that there might be life after death, a heaven and a hell without saying it, suggesting that to him at least, dreams, both good and bad, might have more permanence than they do in a normal sleep. Twain has also commented on the strangeness, to him at least, that more people don’t commit suicide, choosing to cope with existences that were tragic and doomed to die anyway, rather than end it of their own free will, at time and place of their choosing. In this, he was clearly inspired by Shakespeare at points, such as when he noted “Unfortunately none of us can see far ahead; prophecy is not for us. Hence the paucity of suicides,” but typical of the satirist, he went on to claim more than once that those who committed suicide were indeed the sane and in contrast, those who didn’t insane, turning the traditional notion upside down. At least three times, he commented on it this way, “Suicide is the only sane thing the young or old ever do in this life,” “But we are all insane, anyway…The suicides seem to be the only sane people,” and “Of the demonstrably wise there are but two: those who commit suicide, & those who keep their reasoning faculties atrophied with drink.” Also like Hamlet, he ascribed the fear of ending our lives in terms of lacking the courage to do so. Later in the speech, Hamlet remarks that “conscience doth make cowards of us all, And thus the native hue of resolution Is sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought, And enterprises of great pith and moment With this regard their currents turn awry And lose the name of action.” While he had likely shifted from contemplating suicide to his own inability to enact his revenge against this uncle at this point, the statement retains a double meaning. If anything, Twain was more blunt. “You see, the lightning refuses to strike me — that is where the defect is. We have to do our own striking, as Barney Bernato [a diamond magnate, who died at sea under mysterious circumstances] did. But nobody ever gets the courage till he goes crazy.” In his autobiography, which was not released until 2010, a century after his death, Twain even takes aim at those who would try to stay someone’s hand, preventing them from committing suicide, what most would consider it saving their lives. “I would not be a party to that last and meanest unkindness, treachery to a would-be suicide. My sympathies have been with the suicides for many, many years. I am always glad when the suicide succeeds in his undertaking. I always feel a genuine pain in my heart, a genuine grief, a genuine pity, when some scoundrel stays the suicide’s hand and compels him to continue his life.”

While I am neither Hamlet nor Mark Twain, I would humbly add one more parallel between sleep, dreams, and death. Forget knowing what happens after we leave this world for the undiscovered country, we cannot even know what dreams will come in a normal sleep, will they be comforting or unsettling, realistic or a jumbled hallucination, happy or sad, pleasant or an outright nightmare? What realms will we travel, dark or light, ugly or beautiful? Who will we meet, loved ones or twisted ones, those who wish us well or who cause us harm? We cannot say and we have no control. In this way, sleep and dreams are parables of life itself.

Very interesting take; but are you okay? That’s pretty dark. Unfortunately, many smart, creative, independent thinkers agree. Not the least of which was David Foster Wallace. However, he thought it was fear of failing (in suicide) that held back many – not fear of what happened next. It was ending up not dead, but maimed or crippled.

Dreams … have you read Freud and Jung?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, I appreciate it and, yup, I am completely fine, some might say better than ever as I am heading out to Key West tomorrow, then the Carolinas on Friday.

🙂

The opening of this post came to me while I was unable to sleep in Dubai last week. It wasn’t in a dark sense or anything, though I can see why some would think so, but I usually have no trouble sleeping and was jet lagged. For some reason, the abstract thought that it would be easier to kill myself than get some sleep crossed my mind, and then of course I tied it back to Shakespeare and interestingly, I am reading a Mark Twain bio, and his stuff resonated, so I rolled it all together.

Regarding Jung and Freud, not in the source material – I am only vaguely familiar with both, to be honest.

LikeLike

Glad to hear that 🍻

LikeLike