There’s a lesson here for modern filmmakers, who seem positively obsessed with developing backstories, explanatory and obligatory rules, and more in the service of some kind of world building, as though every film must exist in some kind of broader universe with a meaningful beginning, middle, and end.

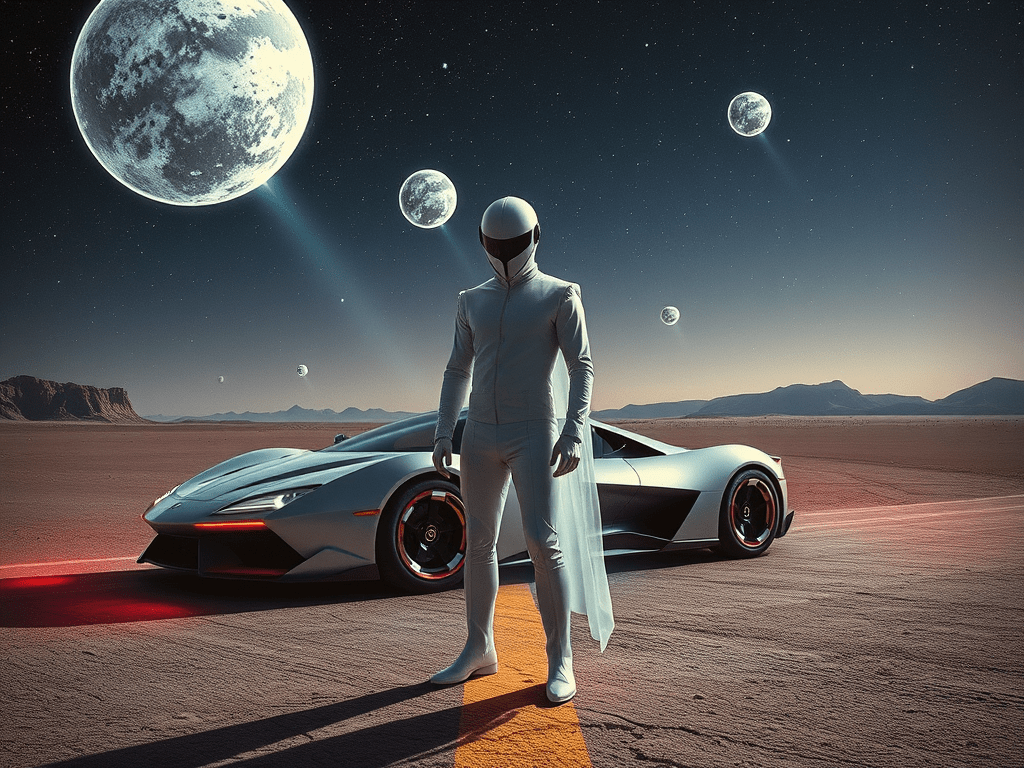

The Wraith, starring Charlie Sheen and Sherilynn Fenn, isn’t a great movie by any means. Released in 1986, it didn’t win any awards and will not be featured on any top films of all time list, even if you reduce the scope to a specific genre or sub-genre, nor will critics be debating whether it should have been on such a list. The plot, to the extent that there really is one, is borderline nonsensical: A teenager is killed by a gang of drag racing thugs, only to return somehow, apparently from space, as a ghost with a futuristic car to wreak revenge, win back the girl, and set his brother’s life straight. The mechanism behind all of this isn’t remotely explained. If he’s a ghost, why does he need a car and how does he get the babe, or even want the babe in the first place? The film doesn’t even attempt to answer these questions, or consider any of the other implications. Instead, much like John Carpenter’s cult classic Christine from earlier in the decade, which may well have been an inspiration along with many another, likely superior film, it proceeds with the assumption that any answers are irrelevant because none of this is real in the first place and the audience probably doesn’t care anyway. Thus, we only need to know two things at the start of the movie. First, that something has returned from the great beyond with a really cool car. This something, whatever it may be and however it fits into the story, is depicted as multiple asteroids or balls of light descending from a night sky, only to connect at a crossroads in the desert where the silhouette of a figure with a helmet, in some kind of suit, beside the vehicle in question. Second, there are some bad dudes, presumably in this same desert. This, we learn, when an innocent couple is driven off the road, forced into a drag race for the title to their car, and then when the boyfriend is about to win the race against all odds, the bad guys cheat, take the car anyway, and leave the poor couple alone on the highway at night.

From these rather thin beginnings, the story begins to emerge. In the next scene, we are introduced to teens at a local reservoir. Charlie Sheen’s Jake Kesey arrives on a dirt bike, a stranger to the town who befriends the younger brother of the man he will avenge, Billy, and promptly starts hitting on his former girlfriend, Keri. While the new kid in town might be a standard of the teen hijinks movies popular at the time, we know something is different about Jake because, in an obvious callback to Clint Eastwood’s Pale Rider, he has a series of scars on his back too noticeably presented for the audience to ignore. The lead gang member, Packard, covets Keri, however, and immediately takes an unhealthy interest in Jake, setting the stage for the primary rivalry that will drive the film, pardon the pun, because all of this, whatever its merits, is primarily a vehicle for racing scenes and other automotive destruction in addition to showcasing an 80s heavy metal and hard rock soundtrack featuring everything from Ozzy Osbourne to Billy Idol with Robert Palmer sandwiched in the middle. Shortly after this meeting at the reservoir, the next automotive theft disguised as a drag race is interrupted by the arrival of the supercar from the opening sequence, technically a Dodge M4S Turbo Interceptor, deployed primarily because of its futuristic shape. Having sold Dodge’s about a decade later and owned one, my first new car, a 1995 Neon, I have some concerns about the engineering and the overall quality of the brand, but for purposes of this film, the Turbo Interceptor certainly looks the part, combining the classic mid-engine, lean-forward stance with a clean, spaceship shape that refused to yield to the contemporary trend of festooning a vehicle with wings and ducts to make it aggressive like a Lamborghini Countach. The hint of an almost truck-type suspension poking out beneath adds a little more exoticism, making it at least somewhat believable that the car has capabilities others simply can’t match. Even so, strange things are afoot when during the very first drag race, the supercar pulls far ahead and the gang member somehow crashes into an image of it sitting perpendicular in the middle of the road, dies in a fiery crash, only to leave behind an unburned body with his eyes removed.

Of course, none of this makes any logical sense, nor do I believe it’s really supposed to. Instead, following the pattern of the entire film, it’s a cause for a race, an explosion, a snippet of great song, and for the local police to get involved, led by Randy Quaid’s Sheriff Loomis, which in turn introduces a mystery aspect to the proceedings. Loomis is also aware that Keri’s boyfriend has been murdered and though he suspects Packard and his gang, the details are vague and there’s no real evidence tying him to the crime. Through a short series of flashbacks that might well be out of place compared to the rest of the tone, if anything can be said to be out of place in this kind of mashup, we learn that Keri witnessed the entire thing, but is too afraid to talk. Packard, a cartoonish combination of a tough guy in the era and a slightly psychotic, creepy love sick fool, provides more than enough reason for her to remain silent, up to and including physically threatening her while professing the depths of his feelings. Perhaps, he is best seen as a more menacing version of Back to the Future’s Biff Tannen, continuing the theme of making callbacks to what most would consider superior films, transformed from a high school bully into a town-wide monster. While Biff, at least in the first film, was a relatively harmless fool with a bark worse than his bite, ready to be put down once someone had the courage to confront him directly, Packard will require significantly more violence to deal with. This is made plain when Jake’s younger brother, Billy, tries standing up to him in front of half the town, only to get mercilessly beaten while the town itself looks on, doing nothing in an inversion of Back to the Future’s climax at the Enchantment Under the Sea dance. If Billy was looking for his moment, he got something different than he hoped for. Meanwhile, Keri unsurprisingly develops feelings for Jake, not realizing that he is the ghost of her former lover for obvious reasons. For his part, in between wooing Keri, Jake continues to wreak havoc on the drag race gang, assaulting the garage that serves as headquarters, literally driving the supercar straight through it, getting out of the car in his suit, and taunting them, causing the requisite 1980’s explosions before killing two additional gang members. This, apparently, is enough for the gang’s tech geek, Rughead, an obvious stand-in for Bugger from Revenge of the Nerds, to flee, confessing to Loomis that Packard killed Jaime, though he wasn’t there and didn’t know the details.

At this point, Packard himself realizes his time in the town has come to an end, kidnaps Keri at knife point, and heads to California. When Keri attempts to flee, Jake arrives in the supercar and challenges Packard to a race, which obviously results in Packard’s death in another fiery explosion leaving him with the same dead eyes as his deceased gang members. Jake proceeds to take Keri home, where he reveals that he’s a reincarnation of her former lover, telling her that he came back so they can have another chance, as opposed to simply wreaking havoc-inducing revenge, presumably. Regardless, he has one more thing to do before they can be together forever as they should have been. He visits, Billy, still recovering from his Packard beatdown, and tells him he should know who he is already. Then, he gives him the keys to the Dodge supercar, and rides off into the sunset on a motorcycle with Keri. Loomis watches these scene unfold, somehow satisfied that the story had a happy ending. Just as presumably, the audience is satisfied as well, provided they don’t start asking questions about what they’ve just seen for the past ninety or so minutes, and simply enjoy the film for what it is: An excuse for cool cars, explosions, and good music supported by a plot that makes no sense in they way its actually told. Revenge tragedies, as a genre, are nothing new, dating back at least to ancient Greece, whether a living person takes revenge or some kind of spirit. Teenage love stories, of course, weren’t a recent invention either, whether of the more classic variety or the 80s rom-com-coming-of-age mash up. Action movies might have been a more recent phenomenon, but it’s not as if audiences at the time wouldn’t have been familiar with car-oriented classics of the genre like Bullitt. At its best, The Wraith blends all of these together, picking and choosing from a disparate collection of arguably better films in the service of nothing more than entertainment. Perhaps not surprisingly, critics haven’t been particularly enthused either then or now, earning a measly 33% on the popular aggregator site Rotten Tomatoes. Mike Massie lamented, “Most of it is simply far too predictable and inconsequential, working from the flimsiest of premises,” while David Nusair claimed it was “a sluggish thriller that suffers from a lack of cohesiveness in its half-baked narrative” and TV Guide called it “A ridiculous mishmash of drag racing, ghosts, and science fiction.” They are not entirely wrong, but appear to be missing the point. While I wouldn’t claim the filmmaker, writer and director Mike Marvin, whose other 80’s credit is Hamburger: The Motion Picture, is an Alfred Hitchcock level talent by any means, it certainly seems clear to me that he understood what he was doing, the purpose of it all, and how the audience would react. Therefore, critics like David Keyes, who claimed “It does not achieve the same absurdist grandeur of, say, ‘Sky Bandits’ or ‘Mannequin,’ which are essentially live action cartoons. But it means well,” Felix Vasquez, Jr, “The kind of revenge B movie you can enjoy thanks to its eccentric tone and unique hero,” and Chuck Rudolph, “An enjoyably trashy sci-fi/car racing action movie,” get closer to the truth in my opinion.

Regardless, it seems to me that there’s a lesson here for modern filmmakers, who seem positively obsessed with developing backstories, explanatory and obligatory rules, and more in the service of some kind of world building, as though every film must exist in some kind of broader universe with a meaningful beginning, middle, and end. Everything these days has an “origin story” whether or not the story is meaningful. The venerable Spider Man franchise, for example, starts when a teenager is bitten by a radioactive spider. Hollywood has seen fit to tell it at least three times despite the extent lasting barely a sentence. The result is an explosion of bloat and exposition, transforming what should be a ninety minute thrill ride into a two hour or longer slog, and some serious mumbo jumbo that will be immediately forgotten after leaving the theater or stopping the streaming service. Beyond a few specific cases, none of it really matters and all of it is useless anyway. In a world where ghosts don’t exist, much less ghosts with cars, any explanation is bound to be both thin and meaningless in the long term, meaning the audience isn’t likely to care assuming they remember in the first place. Instead, they are likely to want to be entertained, however mindlessly. The Wraith, at its best, plays directly into this notion, both trusting the audience to follow along with what can’t be explained and hoping they won’t ask any questions in the meantime. There’s an earnest simplicity to it – knowing the audience will connect with other films it’s culled from, will accept the absurd in service of fun, and will actually enjoy the easy slipping between various genres because it moves so fast there’s no time to think in the first place that is largely missing from modern filmmaking. Besides, who can’t love a movie that ends with a teenager getting a supercar for no apparent reason and no explanation why the car is even real in the first place? Why does such a gift need to be explained in the first place?