Last week, Tucker Carlson interviewed a historian who claimed the legendary Prime Minister was the chief villain in World War II, more responsible for the war than Hitler. Previously, progressives condemned him as a racist retrograde, nor is Churchill alone. The incessant need to continually re-evaluate the past infects both the left and increasingly the right, consuming every discipline from history to literature with mathematics and science in between.

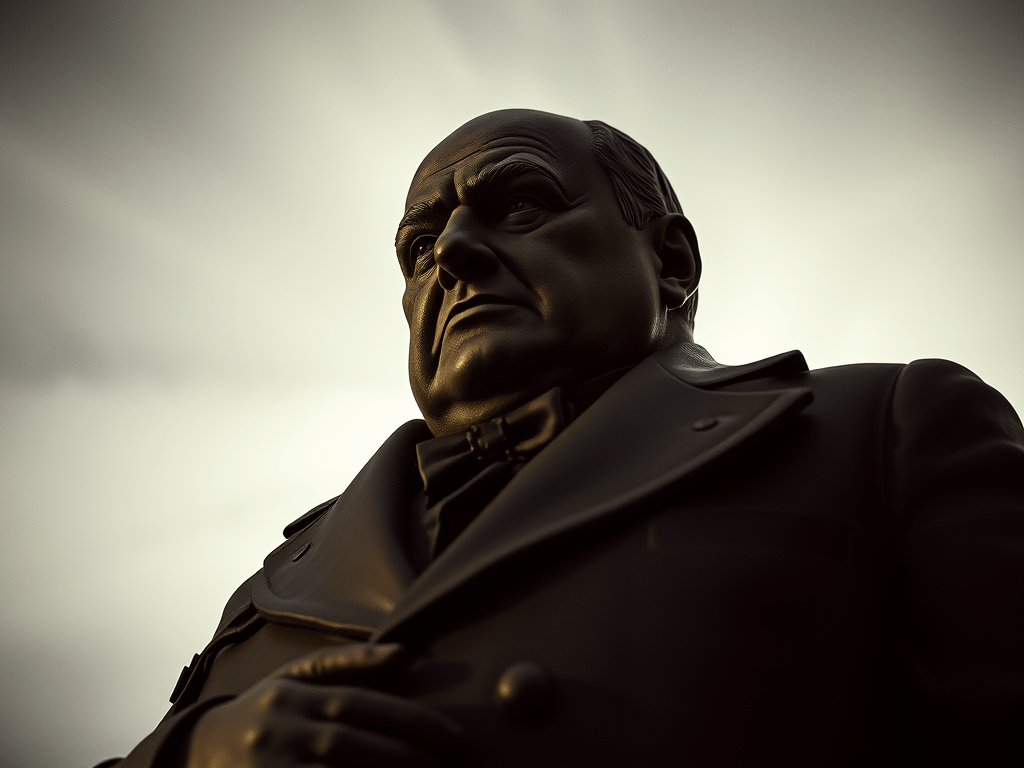

Winston Churchill was a giant, a man whose achievements are legendary, beyond dispute or at least certainly should be. Long revered as one of the greatest leaders in British history and one of the greatest statesmen of the 20th century, he lead his country through their darkest hour, literally the title of a movie where he’s the main protagonist, defending against a barbaric Nazi onslaught targeted at British civilians and rallying the free world to defeat the menace before it had spread beyond continental Europe. By the time the Nazi’s began their infamous blitz in 1940 leading up to the Battle of Britain, essentially a prolonged series of mass aerial assaults designed to break the people’s will and enable German troops to sweep across the country, Germany had already annexed Austria and violated a peace agreement, the Treaty of Munich signed in 1938, which exchanged contested regions in Czechoslovakia for no further encroachment by the Nazis in Europe. The British Prime Minister at the time, Neville Chamberlain, referred to the agreement as “peace with honor,” but Churchill wasn’t deceived by Adolf Hitler’s obvious plan to buy time to build the German war machine, declaring “You were given the choice between war and dishonor. You chose dishonor and you will have war.” It took less than a year to prove him right: Hitler took all of Czechoslovakia in 1939, signed a nonaggression pact with Russia, invaded Poland, and by 1940 had moved onto Denmark and Norway, then France, Luxembourg, and Belgium. After Italy became an Axis power under Benito Mussolini, continental Europe with the exception of some parts of Spain was entirely under Nazi control. Britain had a choice, fight, or be swept away, and given the ferocity of the Nazi’s, an engine of death armed with devastating new technology and capable of unleashing destruction unseen in all of human history, it would have been easy to forgive them for simply surrendering. If no one in Europe could stand against this power, how could a tiny island at the tail end of a crumbling empire? Churchill, however, had an indomitable spirit and correctly realized that the United States would ultimately have to enter the conflict – if the United Kingdom could survive that long, and so he led Britain throughout more than six months of devastating attacks designed to both kill and spread fear and chaos. Between September and October 1940 alone, the Luftwaffe conducted 56 raids on 57 days and nights. A total of 40,000 British civilians were killed, about half of them in London, where a million buildings were destroyed or damaged, but still they didn’t surrender, and less than a year later, Japan bombed Pearl Harbor, bringing the United States into the war with our unmatched capacity for military might. At that point, Hitler had almost inexplicably violated his pact with Russia, believing Joseph Stalin couldn’t be trusted to supply them with oil, pushing the Russians into siding with the Allies. Churchill spent the rest of the war as a partner between the uneasy relationship of Franklin Delano Roosevelt and his Russian counterpart, risking his life repeatedly simply to travel to the summits where the future of the entire world was discussed.

If this was the man’s only achievement, he’d still be a legendary leader by all rights, but Churchill was also a prolific author, journalist, master orator, and soldier. In 1899, he traveled to South Africa to cover the Second Boer War on behalf of the Morning Post, where he was taken captive and held in Pretoria, only to stage a daring escape, sneaking out of his military prison, hiding in a mine, and surreptitiously boarding a train to Portuguese East Africa. After, he returned to the fight as a lieutenant in the South African Light Horse Regiment, joining the battle to take Pretoria itself and end the Siege of Ladysmith. He was among the first British troops to breach both places, even as he urged his fellow Brits not to indulge their racist stereotypes and to show “generosity and tolerance” in their victory. Largely as a result of the fame he achieved during the war, he secured a seat in Parliament in 1900 at the tender age of 25. Incredibly, he published one of his first book that month, Ian Hamilton’s March, about his experiences during the war, and toured America and Canada for the first time later that same year, meeting the likes of Mark Twain, President William McKinley, and Vice President Teddy Roosevelt, who he was said to not get along with despite the obvious similarities in their backgrounds, Renaissance intellects, and common interests in Western Culture (perhaps it was the one’s affection for alcohol and the others distrust). Throughout his career, he authored dozens of books (43) including seminal volumes on the histories of English speaking peoples, the history of World War I, and World War II, almost all while serving his country in almost every capacity. He was President of the Board of Trade in 1908 to 1910, making him the youngest cabinet member in half a century, where he resolved labor disputes, established a Standing Court of Arbitration, and pursued much needed social reform. He was Home Secretary from 1910 to 1911, controlling both the prison and police, where he entirely reformed the prison system including separating prisoners by violent and non-violent crimes, building a system of libraries, offering some form of entertainment, and abolishing maximum security prisons for young people. He commuted death sentences, and was a supporter of a woman’s right to vote. He was First Lord of the Admiralty in 1911 and credited with modernizing Britain’s Navy in the lead up to World War I, while pushing for higher pay and more recreational activities for the Navy seamen. He was an early supporter of aviation as well, leading the construction of the first 100 Navy seaplanes, a term he is credited with coining. After another stint in the military during the war, where he was stationed at the Western Front, he rejoined the cabinet under another Prime Minister as Minister of Munitions, then Secretary of State for War and Air, Secretary of State for Colonies, and finally Chancellor of the Exchequer. In summary, there was almost no aspect of the British government he wasn’t involved in even more than decade before the second world war, and where he frequently pushed forward-thinking reform proposals. By the time World War II broke out and he was catapulted to the heights of power, he’d already transformed much of life in the British empire, nor was that his only stint as Prime Minister, he served again in the early 1950s.

The word “monumental” barely begins to describe his achievements. If Teddy Roosevelt once noted that he was content to die at 60 because he’d lived ten lifetimes, consider that Winston Churchill made it until 90 years old, authoring more books and serving his country far longer than even the American icon. Of course, this doesn’t imply Churchill was perfect. He was a human being like everyone else, and subject to both his own flaws and the capacity for error. If even Sir Isaac Newton and Albert Einstein made mistakes understanding the implications of their own theories in fields as black and white as physics, we should only expect a politician to make many more. On key questions, particularly related to home rule in India, Churchill’s opinions on race and colonialism are wildly out of step in our anti-colonial era, which has undoubtedly led to a previously progressive driven backlash against the great statesman. In March 2021, Priyavada Gopal captured this perspective for The Guardian, writing “Why can’t Britain handle the truth about Winston Churchill?” “A baleful silence attends one of the most talked-about figures in British history. You may enthuse endlessly about Winston Churchill ‘single-handedly’ defeating Hitler. But mention his views on race or his colonial policies, and you’ll be instantly drowned in ferocious and orchestrated vitriol. In a sea of fawningly reverential Churchill biographies, hardly any books seriously examine his documented racism. Nothing, it seems, can be allowed to complicate, let alone tarnish, the national myth of a flawless hero: an idol who ‘saved our civilisation’, as Boris Johnson claims, or ‘humanity as a whole’, as David Cameron did. Make an uncomfortable observation about his views on white supremacy and the likes of Piers Morgan will ask: ‘Why do you live in this country?’” In her view, “Thanks to the groupthink of ‘the cult of Churchill’, the late prime minister has become a mythological figure rather than a historical one. To play down the implications of Churchill’s views on race – or suggest absurdly, as Policy Exchange does, that his racist words meant ‘something other than their conventional definition’ – speaks to me of a profound lack of honesty and courage. This failure of courage is tied to a wider aversion to examining the British empire truthfully, perhaps for fear of what it might say about Britain today. A necessary national conversation about Churchill and the empire he was so committed to is one necessary way to break this unacceptable silence.” There is undoubtedly some truth to what Ms. Gopal wrote, Churchill was a proud proponent of the greatness of Britain specifically and Western Culture in general, but so what? Is it remotely surprising that an aristocrat born in the late 19th century would hold racist views, anymore than we should be shocked that a genius like Charles Darwin did the same a few decades earlier? The entire world at the time, including the most progressive leaders, were retrograde in these views by modern standards. This doesn’t mean it’s unfair to point out the obvious differences between their world view and ours — as every modern biography of Churchill or for that matter George Washington, Abraham Lincoln, Teddy Roosevelt and every other consequential leader does — but what we are supposed to do with this knowledge is entirely unclear. Revere him less for being human and a product of his time? Hate the man for it? Erase him?

As a conservative, this phenomena was relatively easy to dismiss as another example of the progressive predilection for revisionist history, where everything is looked at through a racialist lens and no one measures up, but far more recently, it appears some on the right are starting to fall prey to what we can best describe as “ankle-biting,” that is nipping at the heels of giants simply to bring them down, as well. Last week, former Fox News host Tucker Carlson interviewed podcaster Darryl Cooper for “The Tucker Carlson Show” on X, claiming he was the United States’ “most important popular historian.” Mr. Cooper promptly identified Winston Churchill as the “chief villain” in World War II rather than Hitler, though he gracefully fell short of claiming the British Prime Minister personally set up the concentration camps and implemented the final solution to eradicate all the jews in Europe. Instead, the plan to kill the Jew was merely the result of bad logistics because they had no means to care for the millions they’d kidnapped and tortured. Either way, Churchill, rather than Hitler, was “primarily responsible for that war becoming what it did.” “Hitler starts firing off peace proposals to Britain and France because he didn’t want to fight them,” Mr. Cooper explained. “Churchill wanted a war. He wanted to fight Germany. The reason I resent Churchill so much is that he kept this war going when he had no way to go back and fight it.” “Fall of 1940… Adolf Hitler is firing off radio broadcasts, giving speeches, sending planes to drop leaflets over London, trying to get the message to these people that Germany doesn’t want to fight you” as if we shouldn’t simply interpret this as more obvious propaganda. From that rather dubious assertion, Mr. Cooper proceeded to accuse Churchill of terrorism, “He was literally, by 1940, sending firebomb fleets, sending bomber fleets to go firebomb the Black Forest, just to burn down sections of the Black Forest. Just, just rank terrorism,” he said in a more bizarre and misguided reading of history than any of Churchill’s progressive detractors have done so far. By 1940, Britain and France had already declared war on Germany. They did so in 1939, two days after Hitler invaded Poland, before Churchill was even elected Prime Minister, meaning Churchill inherited a country and a Europe already at war against a deadly, maniacal enemy. In the first year he was Prime Minister, he faced the Blitz, the daring escape of the British military at Dunkirk, Italy entering the war, and France getting crushed. For his part, Hilter had already violated Chamberlain’s peace with honor. What was Churchill supposed to do, trust him again after he’d taken most of Europe and assume he didn’t want anymore? This doesn’t imply that every tactical decision Churchill made was correct, but Mr. Cooper isn’t quibbling with how a certain battle or even an entire campaign should’ve been handled even if I had the expertise to comment on it. Similar to progressives but worse, he’s making a statement that calls into question Churchill’s fundamental character and leadership. If you believe he’s the chief villain in the greatest cataclysm of human history, you are implicitly asserting that the prevailing opinion that he was among the greatest leaders of the 20th century is fundamentally false. Therefore, he should be a subject of scorn rather than admiration.

Why? Churchill is, of course, not alone. This incessant need to continually re-evaluate the past infects both the left and increasingly the right, consuming every discipline from history to literature with mathematics and science in between. We’ve all witnessed statues of legendary, hugely influential figures being torn down at best, moved or updated with a trigger warning at worst. We’ve all seen academics and journalists attempt to rewrite everything from the nation’s founding to the history of roads. I’ve heard right-leaning libertarians declare that Abraham Lincoln was a tyrant. I’ve seen progressives urging everyone to decolonize everything, up to and including canceling William Shakespeare, all as though we were the first culture in history to realize that humans have made progress over the centuries, improving our physical and intellectual condition as time marches on. When James Madison and the Founders modeled key aspects of the Constitution on Roman and Greek democracy, standing on the shoulders of Cicero and other statesmen of the era, they did so under no illusion that any of their inspirations had achieved perfection. As Madison himself put it, “if men were angels, no government would be necessary” but we’re not. Indeed, they admired the political geniuses of the past, but wanted to do something better themselves, learning from their mistakes as we have always done. As humans, we learn and hopefully improve, and yet this doesn’t make Winston Churchill any less of a giant or our penchant, first from the left and now from the right, of biting at his ankles any less disturbing. What is it about the modern world that we simply can’t seem to accept greatness? That we must deny it or destroy it? For centuries, we looked to the giants of the past to inspire us to new heights of greatness in the present, literally and figuratively standing on their shoulders, but today our malaise is such that we, or least many among us, no longer believe great days lie ahead. Frustrated that we feel our future is bleak, beyond our control, subject to powers that seek to do us ill, we are turning to the past, not for hope and inspiration as previous generations did, but to level the playing field, making them as small and miserable as we are. This is not the way to a brighter future. It is a plague that will bring upon us a world even darker than the past.

“we simply can’t seem to accept greatness? ” I recently read in ‘The Baseball 100’ that Hank Aaron wasn’t content with his career b/c he never won The Triple Crown.

Posnanski writes: “This is at the heart of human nature, I guess. I don’t believe anyone has had a more perfect career than Aaron–perfect in that he never had a down season and he has several of the most important records. but even Hank Aaron wishes he could have accomplished just one more extraordinary thing. ‘

Factor in other elements of human nature – and you’ve got an explanation as to the why. And so …

LikeLike