Henry V was literally and figuratively born in blood, especially as his father became king after starving the former ruler, Richard II. We should probably not spare Richard too much sympathy, however. He was the last of the Plantagenet kings, who rose to power on a tide of violence in the 12th century, violence that lead to the Magna Carta and the foundation of modern democracies today.

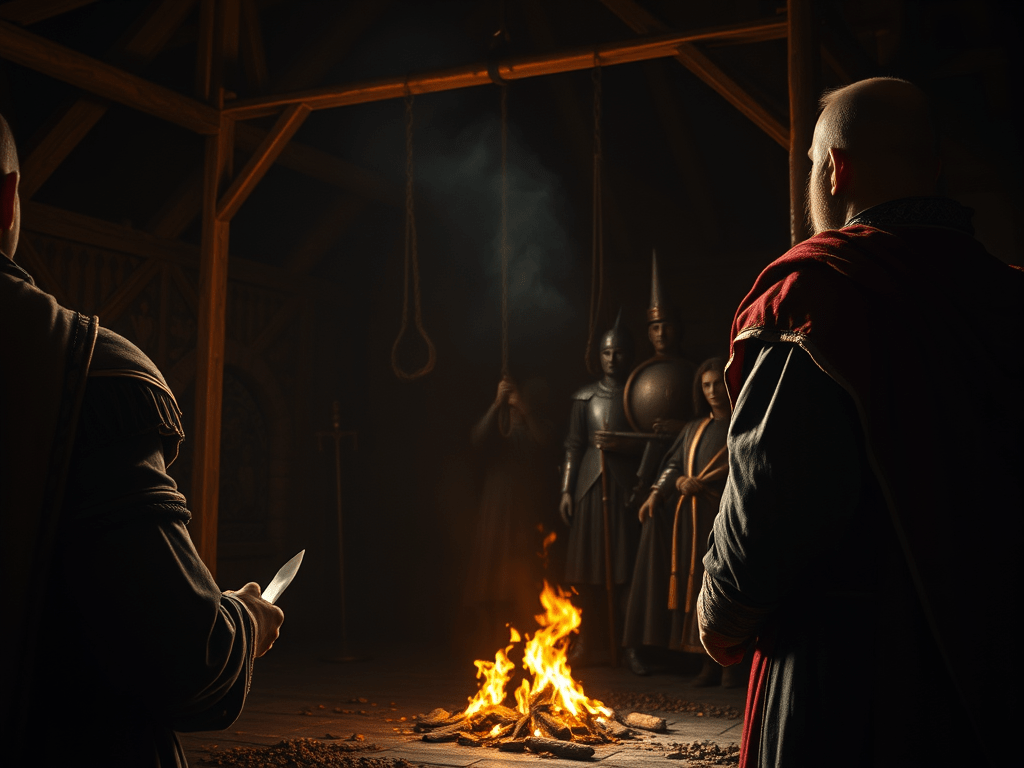

In medieval England, the punishment for treason was death by hanging and heresy death by burning while the criminal was imprisoned in a barrel placed atop a pyre, but what to do when one person is guilty of both crimes? This became more than a theoretical question in the form of John Oldcastle, a heretic who went on to lead a rebellion against King Henry V over six hundred years ago. Oldcastle married into a prominent British family in 1408, elevating himself to Baron Cobham, and was a friend of the king dating back to his time as a prince, described as “one of his most trustworthy soldiers.” By 1410, however, Oldcastle soured on the Catholic church, turning to a protestant doctrine before there were technically protestants, known disparagingly as “Lollards” that challenged key tenets including transubstantiation. He was protected for a time by his relationship to Henry, but in 1413, irrefutable evidence was found in the form of a book at Paternoster Row in London and Henry could deny the situation no longer. Though Oldcastle swore that he would submit “all his fortune in this world” to the king, he could not violate his religious conscience, forcing Henry to allow a trial to proceed. Oldcastle came before the ecclesiastical court in September 1413, refused to repent, was convicted, and sentenced to execution by burning until Henry gave him a 40 day reprieve to reconsider. During that time, he escaped his bonds, aided by a man named Willian Fisher, and put himself at the head of a rebellion, raising an army of Lollards that fought with the King’s forces on St. Giles Fields on January 10, 1414. The Lollards were crushed, but Oldcastle escaped and remained a renegade until 1417. After he was taken to London, he was formally convicted of both treason and heresy on December 14, then sentenced to execution on the same day, but how can you kill man twice and in what order should you do it, hang first then burn or the other way around? They settled on a devilish solution: Do both at once, and so they devised a barrel that sat underneath the gallows, lighting him up from below, and then yanking him up from above to the presumed delight of the crowd. Nor was this Henry’s first burning. While still prince, John Badby was convicted of being a Lollard as well, a tailor from Eversham who captured the English imagination. On March 5, 1410, he was sentenced to death by burning in Smithfield, not far from London. Given the interest from the public, Henry chose to attend in person. Though Badby had been imprisoned under brutal conditions for a year and had refused to repent, he was offered one more chance. As late as March 1, he’d informed the Archbishop that Catholic practices were so misguided, he’d tell Christ himself that “if every piece of bread consecrated on every altar in England turned into a bit of him, there would be twenty thousand Christs roaming around the realm at once” to use the words of Henry biographer and historian, Dan Jones. Even in the barrel itself, he refused to reconsider, when asked what he made of the host, he shot back “Holy bread and not God’s holy body.”

At that point, the executioner approached the pyre, setting it aflame with a torch. In mere moments, the barrel was burning with Badby in it, but while he was screaming in his death throes, before he succumbed to smoke inhalation, Henry ordered the pyre kicked away and the barrel opened, offering the poor man, who a chronicler described as half-dead, one last chance that “he should keep his life and obtain pardon and receive three pence daily from the royal treasury for the rest of his life.” Incredibly, Badby refused this final reprieve, so a grim Henry ordered him back in the barrel and the pyres lit once more, “And so it happened that this meddler burned to ashes there in Smithfield, miserably dying in his sin.” At the time, Henry wasn’t yet 25 years old, and even this wasn’t his first execution. As far as historians know, Henry personally ordered a group of rebels in Wales to be “drawn and then disemboweled, hanged, beheaded, and quartered” at the tender age of 14. These atrocities occurred following a sudden uprising, when Conwy Castle was taken over by around 40 Welshman after a traitorous carpenter tricked the guards into letting him in. They were able to hold the castle against a siege for two months. After Prince Henry arrived, the leader of the rebels, Gwilym ap Tudor ultimately agreed to hand over nine hostages in exchange for royal pardons for their treasonous behavior. While Henry wasn’t able to violate the terms of the agreement, he knew he needed to make a statement and nothing was specifically said about what became of the hostages after the exchange. Fearing no punishment at all would be seen as weakness, he personally ordered their gruesome deaths – while Tudor and the others who were pardoned watched. No one knows for sure how he felt about this. Henry’s “character” is known more from the legend created by William Shakespeare in his timeless play than in real life, but there are no records of any qualms or regrets of any kind. Perhaps the best we can say is that his father, King Henry IV, was pleased, regarding the incident as a vital lesson for his “most beloved” heir and didactically informing him “remember, dear son, that it is cheaper and easier to defend a castle than to reconquer it once it was lost.” Henry himself was no stranger to personal injury either. Shortly after Conwy Castle, one of Henry’s comrades who was part of the siege, Hotspur, turned traitor (note the recurring pattern in these savage times), prompting a savage battle, the first that pitted English upon English in over eighty years. At 16 years old, Henry was in the thick of it. While thousands fell, he fought for over three hours and sometime in the middle, must’ve lifted the visor on his helmet, only to be shot in the face, right below the right eye with an arrow, but rather then relent, he broke off the shaft and defended himself against men trying to drag him away. Hotspur apparently believed he could take advantage of the breaking royal line, only to find Henry charging at his flank, encircling his army, and as the moon began to rise, Henry and his father proved victorious.

Hotspur himself lay dead on the field, hacked apart along with his guard, but that was only the beginning of his death march. The next day, while his son lay at the edge of death himself, King Henry IV had Hotspur’s body cut into four pieces and then scattered across the kingdom. Another traitor Thomas Percy was promptly executed, his head sent to adorn London Bridge. Young Henry, meanwhile, lapsed in and out of a coma, the metal tip of the arrow “buried in the furthenmost part of the bone of the skull to a depth of six inches.” Miraculously, he survived, went on to conquer France, during which he slaughtered hundreds of unarmed, defenseless, and mostly injured captives at Agincourt, becoming the most victorious English king in history, only to succumb to dysentery in the field when he was 35 years old. You might say that Henry V was literally and figuratively born in blood. After all, his father only became king after usurping the throne and starving the former king, Richard II to death at Pontrefact Castle. We should probably not spare Richard too much sympathy, however. In addition to sending more than a handful of his own men to horrible deaths, at times in vengeful fits of paranoia, holding grudges that lasted decades, he was the last of the direct line of Plantagenet kings, who rose to power on a tide of almost unprecedented violence in the 12th century, violence that was at times directed against themselves. Henry II, the first Plantagenet king, stormed through England and France, laying waste to everything in his path, only to find himself almost overthrown by his own wife and children. Two of those children went on to become legendary names, representing the opposite sides of kingly virtues to this day. Richard the Lionheart was a legendary crusader, who became legendary primarily for slaughtering thousands in the holy land – and in his own country – before dying of gangrene after receiving an arrow wound while besieging an almost irrelevant castle in France. John was the infamous villain who inspired Robin Hood, depicted as a cruel, vicious, notoriously violent ruler, who died like his descendant, Henry V of dysentery while on a battle march. Yet, as Mr. Jones has noted the difference in historical recognition has been driven mostly by how they were perceived at the time, whether they were successful tyrants or failed tyrants, “John’s reputation is as one of the worst kings in English history, a diabolical murderer who brought tyranny and constitutional crisis to his realm…But was anything he did more grotesque then some of the deeds perpetrated by his much-lauded brother Richard or his father? Probably they were not, yet John’s reputation suffered far more than theirs. In the most sympathetic analysis, John’s greatest crime was to have been king as fortune’s wheel rolled downward.”

Ironically, amid this brutality and perhaps even because of it lies one of history’s greatest achievements in the long, uneven, sometimes backward march towards liberty, freedom, and democratic government: The Magna Carta, which would go on to become the foundational framework for constitutions around the world. Equally ironic given its pre-eminence as a work of legal art in the modern era, it was roundly despised when it was signed in 1215. King John himself promptly moved to have the entire thing annulled by Pope Innocent III before the ink was even dry to use the old expression. Once asked, the Pope himself effectively shat upon the entire enterprise, decreeing that anyone who supported it would be booted from the Catholic church, writing “we utterly reject and condemn this settlement and under the threat of excommunication we order that the king should not dare to observe it and that the barons and their associates should not require it to be observed: the charter…we declare to be null, and void of all validity forever.” Mr. Jones described it this way, “In 1215 the Magna Carta was nothing more than a failed peace treaty. John was not to know – any more than the barons who negotiated its terms with him would have done – that his name and the myth of the document sealed at Runnymede would be bound together in English history forever.” Apparently, those at the time weren’t much interested in fundamental rights like “No free man shall be taken or imprisoned or disseized or outlawed or exiled or in any ruined…except by lawful judgment of his peers or by the law of the land,” or “To no one will we sell, to no one will we deny, or delay right or justice,” or even “no widow shall be forced to marry so long as she wishes to live without a husband.” Their ancestors certainly would be, however, and by the time Henry V took the throne almost two centuries later England had taken critical steps toward constitutional government despite the violence and depravity. In 1236, a rudimentary Parliament of England was formed, a combination of high court, lawmaking body, and tax policy center, at least partially as a result of the Magna Carta’s decree that the king was subject to laws and required “the common counsel of our kingdom.” As a result, the king could still rule with an iron fist, but he could not raise revenue without the consent of parliament, setting the stage for the separation of powers into three equal branches of government we take for granted today. During the reign of Edward III, the commoners began meeting separately from the nobility and clergy in 1341, creating an early version of the Upper Chamber and a Lower Chamber, what would become the House of Lords and the House of Commons in 1544. When Henry took the throne, his father had already extended Parliament’s powers to include “the redress of grievances.” Thus, to paraphrase Thomas Jefferson who would consider some of these matters while pondering American independence more than two hundred years later, the tree of liberty had long been watered with the blood of patriots and in this blood, democracy was ultimately born, most likely because of this blood.