Few, if any endings are more tragic, but therein lies Shakespeare’s clever trick. To produce such an effect, he hid a tragedy in what is truly a comedy, the comedy of life itself.

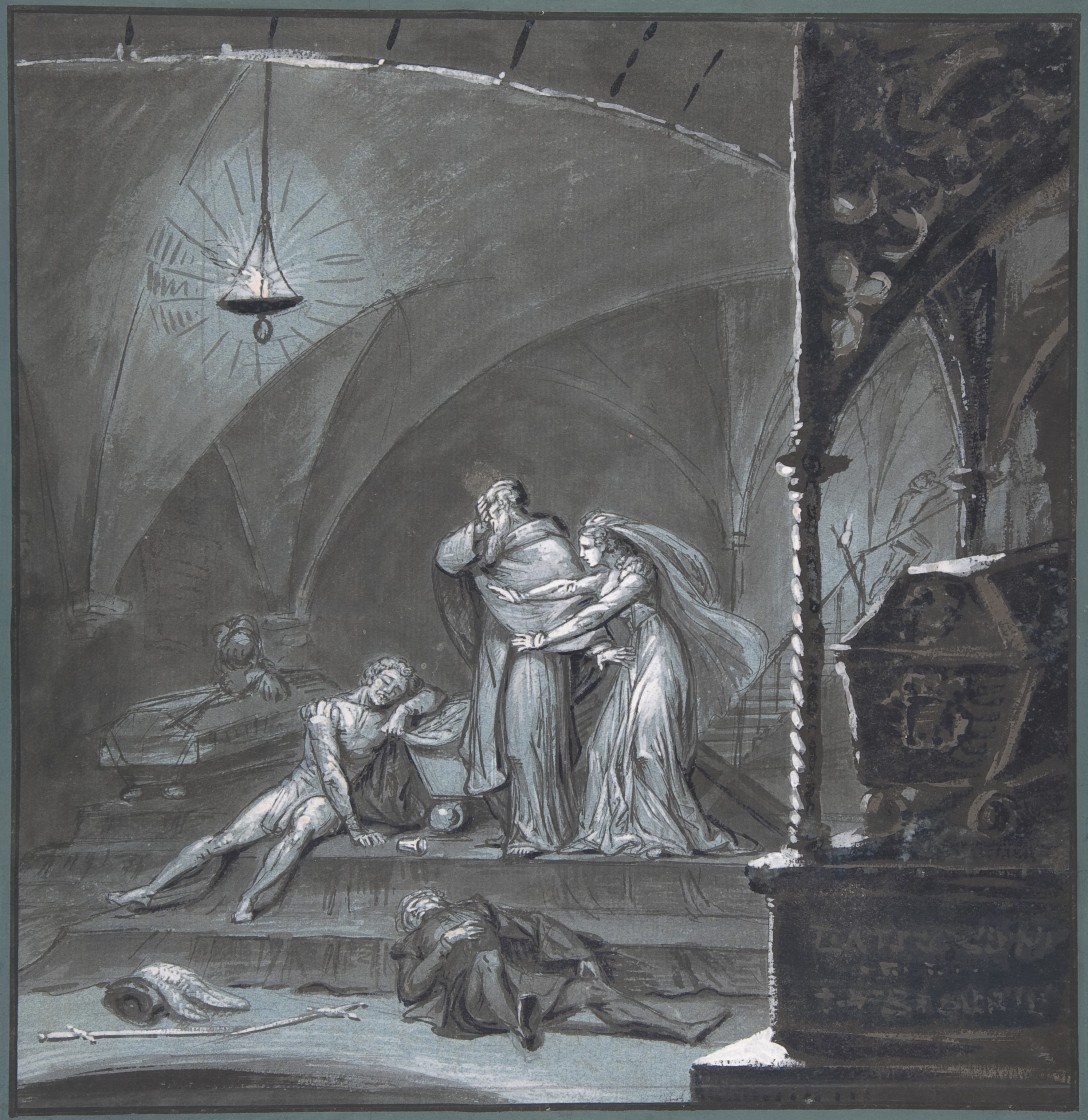

Everyone knows Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet is a tragedy because any play that ends with two young lovers, the main characters of the entire piece, dead by their own hand simply can’t be anything else. Even before the final curtain falls, the word “tragic” barely begins to describe the overall scene. Romeo arrives at Juliet’s tomb in a rage, warning Balthasar that he will “tear thee joint by joint and Strew this hungry churchyard with thy limbs. The time and my intents are savage-wild, More fierce and more inexorable far Than empty tigers or the roaring sea” if anyone gets in his way. Balthasar wisely leaves him be, but Paris is equally lovestruck with Juliet, indeed he was supposed to marry her, and he too seeks to enter the tomb, failing to heed Romeo’s warning “not another sin upon my head By urging me to fury.” Romeo slays Paris, but still the besotted suitor begs him to “Open the tomb; lay me with Juliet.” So blind was Romeo’s rage, he didn’t even know who he killed until he looked him in the face and once he finally recognizes the man that was set to marry his own wife, can’t quite remember his relation to Juliet. He wonders if he was ever told Paris would have married her in his place. “Said he not so? Or did I dream it so? Or am I mad, hearing him talk of Juliet, To think it was so?” Ultimately, it doesn’t matter, Romeo must open the tomb and the tragic loss must continue, piling one death on top of another, and so he discovers Juliet’s body and exclaims:

O my love, my wife,

Death, that hath sucked the honey of thy breath,

Hath had no power yet upon thy beauty.

Thou art not conquered. Beauty’s ensign yet

Is crimson in thy lips and in thy cheeks,

And death’s pale flag is not advancèd there.

The audience, meanwhile, knows Juliet is still alive, that she has faked her own death to be with him, and only an accident of fate has prevented Romeo from being privy to this fact, making us want to scream at the performer, yell at the book in our lap, do something, anything to prevent the inevitable. We are fully aware, however, what must happen next and what will happen next, as sure as we know night will follow day and everything in this world will one day be lost to us. Romeo poisons himself and dies with a “kiss,” only for Juliet to awake and discover his dead body. She is confused at first, wondering “where is my lord? I do remember well where I should be, And there I am. Where is my Romeo?” Friar Lawrence, who was unable to get the message to Romeo that Juliet planned to fake her suicide, has arrived in the interim and can only exclaim, “A greater power than we can contradict Hath thwarted our intents. Come, come away. Thy husband in thy bosom there lies dead” and as Hamlet will tell Ophelia more forcefully in a later play, tells her he will take her to a nunnery, knowing she cannot recover from this loss and has no hope of a normal life. Juliet refuses him as she must, and realizing that there is no poison left, tries to pull some from his lips, “Haply some poison doth hang on them to make me die with a restorative, Thy lips are warm!” As the watch approaches to investigate the disturbance, she grabs Romeo’s dagger, and simply kills herself with barely a word. There is no great speech, no ode to love lost, no recognition of the cruelty of being star-crossed lovers, mere victims of fate and chance, or anything even remotely dramatic except the action. Quickly, instead, she says, “I’ll be brief. O, happy dagger This is thy sheath. There rust, and let me die.” After, Shakespeare expects the audience to find solace in the ending of the feud between the Capulets and Montagues that set these tragic events in motion, likely full knowing no one who ever watched or read the play would think the loss of love, innocence, and life we just witnessed was remotely worth the Prince’s final statement on the matter:

A glooming peace this morning with it brings.

The sun for sorrow will not show his head.

Go hence to have more talk of these sad things.

Some shall be pardoned, and some punishèd.

For never was a story of more woe

Than this of Juliet and her Romeo.

Few, if any endings in all of literature are more tragic – and more well remembered, cited by even those who have never actually seen the play or read the text – but therein lies Shakespeare’s clever trick. To produce such an effect, he, about a third of the way through his immortal career and before some of his even more immortal works, hid a tragedy in what is truly a comedy. Putting this another way, Romeo and Juliet has a tragic ending, but in structure, form, and characters it is much closer to a comedy where the lovers meet and live happily ever after following some dramatic conflict. Comedies in Shakespeare’s era were closer to romances or romantic comedies in ours, generally defined by the meeting of the young lovers, how they become besotted with one another, some kind of satirical or comic exaggeration to the language or the performance, a comic villain, and a misunderstanding that causes strife followed by a happy ending. A formula that hasn’t changed much to this day, still readily recognizable in the likes of When Harry Met Sally, Sleepless in Seattle, and other modern movie classics, many of which like the recent Anyone But You are either directly or indirectly based on Shakespeare. Romeo and Juliet, though it was written some four hundred years ago, includes all of these elements, and then some. The couple falls in love before they officially meet, complete with overly dramatic language that borders on satire. Romeo claims that Juliet “doth teach the torches to burn bright,” “she hangs upon the cheek of the night,” and “Beauty too rich for use, for Earth too dear.” The mere sight of her is enough to question whether or not he’s ever loved before. “Did my heart love till now? Forswear it, sight, For I ne’er saw true beauty till this night.”

Needless to say, Juliet feels the same. We might not learn the depths of her devotion and desire until a little later in the play, but at their initial meeting, they flirt and banter in the appropriately playful and exaggerated fashion of the genre, comparing their love to saints and sinners. Juliet remarks, “For saints have hands that pilgrims’ hands do touch, And palm to palm is holy palmers’ kiss.” Romeo implores her to “let lips do what hands do” and they kiss a few moments after meeting, “Thus from my lips, by thine, my sin is purged.” Immediately after, they both learn about the underlying conflict that will threaten their relationship, that they’re families have been enemies for generations, but they don’t care, believing nothing can thwart their love even as the audience knows otherwise. That evening, Juliet considers Romeo from her balcony in the famous, dare I saw iconic, scene, questioning why he has to be a dreaded Montague, but only after Romeo declares that Julie “is the sun. Arise, fair sun, and kill the envious moon.” For her part, Juliet questions what makes a person a person, and an object an object, questions that we have not answered to this day, wondering why Romeo has to be Romeo and love could not be simpler. “What’s in a name? That which we call a rose By any other word would smell as sweet. So Romeo would, were he not Romeo called, Retain that dear perfection which he owes Without that title.” Romeo overhears her of course, and professes his love. Juliet immediately professes hers in return, and they begin a secret relationship that will ultimately lead to their tragic deaths.

The tragic aspects notwithstanding, it’s impossible to mistake the comic form of the entire play except the ending, from the characters to the nature of the challenges they must face. In this case, the conflict that will prevent them from getting together is revealed even before they meet for the first time. The audience knows who Romeo is and who Juliet is before they know themselves. We are even aware that Juliet has another suitor. Romeo and his companion Benvolio only gain entrance to the party by trickery and disguise, suggesting the two would never have met under normal circumstances, fate at work again starting the relationship and ending it. The language of their meeting and their instant falling in love is over the top, bordering on the ridiculous at points – has anyone ever truly proclaimed their love was the sun itself? – but the knowledge the audience possesses that they do not, adds complexity and keeps it from falling into a farce. Comic relief in general will appear sporadically throughout the play, primarily through one of Shakespeare’s most revered early characters, Juliet’s nurse, who is aware of her secret romance and generally steals every scene she is in, complaining about everything, from the aching of her bones to Juliet’s impatience with a savage wit that serves as precursor to the great Falstaff. The nurse teases her charge, saying “You know not how to choose a man. Romeo? No, not he. Though his face be better than any man’s, yet his leg excels all men’s, and for a hand and a foot and a body, though they be not to be talked on, yet they are past compare. He is not the flower of courtesy, but I’ll warrant him as gentle as a lamb.” The friar, who facilitates their relationship and ultimately marries the young couple, serves as a somewhat tragic counterpart, urging them not to love too much in a foreshadowing of the darkness to come before they are wed. “These violent delights have violent ends And in their triumph die, like fire and powder, Which, as they kiss, consume. The sweetest honey Is loathsome in his own deliciousness And in the taste confounds the appetite. Therefore love moderately. Long love doth so. Too swift arrives as tardy as too slow.”

As their relationship progresses, barriers keep piling up – Juliet’s family presses her to marry Paris, Romeo is banished after killing Tybalt, and arrangements are made for her actual marriage to Paris – but their love defies all obstacles, and Juliet comes up with the fateful plan to fake her own death to live on with Romeo in another life. In some other, better world, we can imagine that Juliet’s letter to Romeo informing him of her plan made it through and the two lovers were united forever, beginning anew somewhere, but Shakespeare himself has informed us from the very opening lines that is simply not to be, not in this universe at least. Wisely, he realized that the audience would rebel if the tragic end came without warning, and the young lovers suddenly died when we expected them to live happily ever after. Instead, he lets the us know this will not be a happy play in the prologue, declaring the couple “A pair of star-crossed lovers [who will] take their life” before the action even begins, referring to their “death-marked love” and their “end.” Thus, the audience watches the comedy that ensues, full knowing that the ending will be tragic, heightening the sense that things might turn out differently even though the play is already written and the fateful events are already fixed as the “two hours’ traffic of our stage” the chorus implores us to with “patient ears attend.” Shakespeare, for his part, could only have made these choices intentionally because he made quite different ones in other works that, as was typical for a writer of his unmatched talent, also play with the formulas for both tragedy and comedy. In Love’s Labour’s Lost, for example, the four couples who should live happily ever after are separated at the end by an unexpected war, which functions as something of a deux ex machina, except Shakespeare warned it was coming in the title. Similarly, Twelfth Night ends with the proclamation that there shall be no more marriages until peace is restored, even as we know that’s not possible. Measure for Measure closes with two forced weddings and an uncertain one, All’s Well that Ends Well simply refuses to end well, contrary to its title as Love’s Labour’s Lost was accurate to its.

Crucially, all of these twists on would be comedies including Romeo and Juliet are distinct from the classic approach to tragedy and even Shakespeare’s own approach as the undisputed master of the genre. Generally speaking, tragedy requires two things. The protagonist must have a fatal flaw that brings about their demise. The ending must also be cathartic, either in the audience witnessing the comeuppance of a monstrous figure or through a figure so tormented by fate there is no purpose in their continuing. The deaths that the audience knows will arrive at the end have to mean something, prompting us to reflect on the significance. Romeo and Juliet, however, has neither of these traits. The protagonists have no fatal flaw save loving each other, which is generally viewed as a positive. Their deaths are brought about largely by accident, something which could have been avoided with a little bit of luck. The audience isn’t left thinking about anything or pondering the mysteries of human nature. Instead, they are the equivalent of punched in the gut, feeling it emotionally rather than thinking about it rationally. Shakespeare, meanwhile, undoubtedly knew how to include both of these key elements of a tragedy, perhaps better than anyone else in the entire history of the universe, but even then he frequently preferred playing with the genre as he did everything else. Macbeth’s ruthless ambition turns him into a monster by the end of the play, killing even women and children to preserve his power, and yet the witches’ prophecy and the prodding of his wife make us wonder whether he would have been set on this path on his own. Hamlet’s fatal flaw is of a different and decidedly underwhelming kind: He’s indecisive and thinks too much or either too well depending on your perspective. He meets his tragic end through what we might describe as sheer exhaustion and weariness with the world. King Lear presents a figure that is damned by his own naive obliviousness to human nature, and then dies mired in grief and madness stemming from his inexplicable decision to split his kingdom based on which daughter loves him most. Othello’s jealous nature and, similar to Lear, inability to fairly assess the motives and character of those closest to him leads to his doom. Interestingly, Antony and Cleopatra serve as a unique pair of tragic figures, lovers doomed by pride, as if Romeo and Juliet were truly reimagined as a pure tragedy.

Two things stand out: All of these endings (and others in Shakespeare’s canon) tend to make you think, rather than feel, and none of these flaws apply to either Romeo or Juliet. You are aware that each of these traditionally tragic figures “deserves” their fate in some sense, and largely brought it about through a flaw in their own character. Some might be more monstrous than others, Macbeth being chief among the irredeemable, but all have taken their unique gifts and transformed them into ruin, leaving no shortage of bodies in their wake. Hamlet might stand alone as a character we can imagine worthy of survival, having every reason at the start to seek revenge, but rather than getting on with it, his own failure to act causes the death of Ophelia, Polonius, Rosencrantz, Guildenstern, Laertes, and his own mother, Gertrude. We might not say he deserves it in the same sense as Macbeth. The questions we will ask as we consider how these events unfolded, whether or not they were inevitable, might be different, but we cannot escape that the Danish Prince has blood on his hands. Romeo, of course, kills two people, but the circumstances are different and far more justified. He slays Tybalt after Tybalt taunts him and kills his friend Mercutio. Even after Tybalt flat out calls Romeo a villain, however, Romeo tries to extricate himself from the situation, hinting that he loves the Capulets because of Juliet by saying “the reason that I have to love thee, Doth much excuse the appertaining rage, To such a greeting. Villain am I none. Therefore farewell. I see thou knowest me not.” Tybalt presses the issue and insists that Romeo draw his sword to fight, but Romeo says again that he loves him “better than thou canst devise” and that he has no wish to fight. It is Mercutio, named after the inconstant nature of the god Mercury, who steps into the breach, gets himself killed despite Romeo’s attempts to stop the fight, and only then is Romeo prompted to act. Similarly, he kills Paris in a rage, while not provoked, at least interfered with in a way the audience understands was simply too much for his mental state.

Regardless, I know of no one who has ever claimed that Romeo and Juliet deserved to die, most desperately wish they lived on at the end, and believe that their deaths are filled with emotion, pain, and loss far beyond any coherent thought. We do not question why they died except to say that circumstances were aligned against them in a way they could not match. As the Friar Lawrence said, “a greater power than we can contradict” has doomed them. We can see in this the happenstance that defines our own life in matters large and small, from a child who dies crossing the street to a person killed by a stray bullet on a street corner. Tragic yes, but part of a tragedy no, which brings us back to Shakespeare’s genius, transforming one genre into another even this early in his career, and hiding a comedy with one of the most tragic endings of all time, but isn’t that true of life in general? How many of our plans are foiled simply by luck or chance? How many things that start well are destroyed by conflicts we have no part of? Thus, we also see in Romeo and Juliet something of ourselves, who we wish to be, the love we wish to have even though we are all victims of circumstances in the end. In this regard, the play might be considered the tragedy of life itself. We experience the world as a comedy in our own minds, hoping for that happy ending in defiance of the reality that mostly tragic ones await given our mortal state.

It seems obvious, in my reading, that the tragic flaw of Romeo and Juliet alike is their idolatry. I am a romantic at heart so I respect their ecstatic love, and R & J is one of my favorite plays, but it’s hard me to understand how you can come to the conclusion that their deaths don’t follow that fatal structure of tragedy, including the sacrificial/Girardian scapegoat element of it. In R & J, for instance, the title characters’ death provides for the advent of a world in which they would not have had to die.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for your thoughtful post, much appreciated. Obviously, we can never know what Shakespeare intended, but here are a few thoughts for discussion.

🙂

In my view, I can see what you are saying, but to me at least I find it hard to believe that Shakespeare viewed love as a tragic flaw. You can brand it “idolatry” but there is no other evidence in their characters that was a some kind of general trait, and it only manifested in the context of the play in relation to each other. At least in my understanding, the tragic flaw is normally something that is inherent in a person, not a person’s relationship to someone or something else, especially when their love towards each other is presented as entirely pure, even compared to sainthood in their first meeting.

Regarding the ending, I cannot think of another tragedy, Shakespearean or otherwise, where the deaths are brought about largely by accident. If Romeo had received the letter, none of it would have happened and they would have lived happily ever after, making the conclusion contingent rather than necessary, which is a key aspect of comedy. Shakespeare even manages to sneak in a case of mistaken identity when he doesn’t recognize Paris. Even from an emotional perspective, the audience wants the characters to live happily ever after at the end, as opposed to Macbeth, Lear, or Hamlet to a large extent where it is obvious they need to die. In my mind at least, Antony and Cleopatra provides an inverted version where the story is told as straight tragedy, and the comparison between the two addresses these concerns, especially when you consider that he inserts comedy at the end with Anthony’s three failed suicides — almost as if Shakespeare was messing with his audience, saying you think Romeo and Juliet was a tragedy? Here’s a real lover’s tragedy with a slightly comic ending.

🙂

Regarding Girard, I do not see why we should take thoughts on tragedy developed hundreds of years later and backdate them as opposed to focusing on the original work and the prevailing genres at the time. I think that might be an interesting intellectual exercise, but I am pretty much a straight Bloom/Vendler follower and do not generally include anything outside the work or the immediate context. I could well be wrong, but I don’t find the advent of a new world compelling, nor was that a topic in Shakespeare’s day to my knowledge. He would have been adapting Greek tragic formulas, and while I am not expert, I don’t think that was discussed as an element contemporaneously.

LikeLike

§1 What I might call “my intellectual conversion” transpired—I can remember it plain as day—as an undergraduate freshman. We were in a seminar class on Cervantes’ Quixote and I remember objecting to a symbolic interpretation of events that, in my estimation, the author couldn’t possibly have intended. “Cervantes couldn’t possibly have thought of that when he was writing this chapter,” I said.

My professor looked at me and patiently responded, “Maybe he did, maybe he didn’t. Since there’s no way to verify either way, that can’t possibly be the most important question here.”

His reply struck a sort of epiphany in me and I felt a knot in my heart “Thaw and resolve itself into dew.” Now I think that great artists are inspired by the Holy Ghost, and whether they are conscious of it or not, the spirit of humanity speaks in their words. “Obviously, we can never know what Shakespeare intended,” as you observed, but if we could and you made a better case for an alternative meaning, I would take the latter as veridical. Historical facticity is simply not the correct standard to apply to evaluate the merits of the higher things.

§2 I appreciate your point that their idolatry may not qualify as a tragic flaw. To me, idolatry consists in inordinate love. So it would be idolatrous for Juliet to love Romeo’s little finger above him himself, since he is the cause of his little finger. As a metaphor, if you love a flower, you will not pluck it, but water it, and give thanks to the Earth from which it grows and to God, who created the Heavens and the Earth. I don’t think you have to be religious to understand this principle. So to my mind there is something inordinate about their love because it is too consumptive, and they pay the price.

But I have little interest in defending this interpretation if you don’t find it compelling, so consider two others:

1. Their deaths are not really a punishment but an apotheosis: what is to live immortal in song, must go under in life.

2. It’s a condemnation of this world, since the saintly love that you described can’t but exist as a brief flash before the “rulers of the darkness of this world” extinguish it.

§3 I appreciate your points, but consider how R & J mirrors the structure of Pyramus and Thisbe (watch this, btw, if you haven’t already THE BEATLES – THISBE & PYRAMUS) in respect to the reciprocal suicides. Ultimately, whether you regard their deaths as necessary or contingent hinges on your answer to the question we touched on above in respect to whether they are guilty of a tragic flaw. In a certain light, they have transgressed the positive or worldly order and condemned to pay the price for it, like Antigone. I don’t understand exactly what you mean by “accident” because it’s not as though a tree branch spontaneously fell on their heads. Instead, their respective deaths were motivated by an intentional series of events. But, indeed, the sense that it could have been averted by only a hair’s breadth of difference creates a dramatic irony that serves as an engine of suspense over the last acts.

§4 Fair enough, but I think you have to consider that Shakespeare was not merely adopting Greek formulae, but reinventing and repurposing them. The question of proper hermeneutics touches on a point already expressed above so I won’t belabor it here.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great points, and in general, I agree on your “fair enough” proposition. Obviously, one of the great things about Shakespeare is that different people can read so much into it. I did want to respond two items you asked about:

1) Regarding the “accident.” Romeo would have received the letter and known about Juliet’s plan except for pure chance. Friar John is not able to reach Mantua because he was detained by the authorities who believed he was sick. I could be mistaken, but I cannot think of any tragedy that hinges on this kind of bad luck. The Friar wasn’t even sick. It was strictly a mistake that leads directly to both characters deaths. Without it, they would have survived. In my view at least, that undercuts all other points about whether their love was idolatrous or their existence was a transgression. I am not saying that’s incorrect, but if that were the point Shakespeare was trying to make, one would think he would have come up with an ending that hinged on something relevant, rather than what is essentially a comic mishap, a case of bad timing. It’s not as if he didn’t proceed to come up with some of the greatest tragic endings of all time.

2) Regarding the correct standard of interpretation, to me at least, the text is supreme whether it is intentional or unintentional on the part of the author, given there is no way to discern between the two most of the time. I might be biased in this regard, but I am inherently skeptical of any higher order literary theories or paradigms. I do not want to claim to be an expert on Girard, but I would say there is something similar at play with Campbell’s Journey of a Hero. It’s an interesting idea and it’s worth considering why so many epics and similar works follow that pattern, but each author is unique and none of the authors before Campbell were aware of Campbell. It strikes me as trying to reduce literature to some type of formula, rather an approaching each work as unique. I would also suggest that Paradise Lost is after all the greatest epic in the English language by far, and yet it conforms to precisely none of Campbell’s precepts.

Thanks again for the great discussion, above all I appreciate your taking the time to read and comment.

LikeLiked by 1 person